According to eliminative materialists, the statements ‘I feel pain’ and ‘I believe that the cat is on the mat’ can be reduced to statements about physical mechanisms of the brain. ‘My C-fibres are firing’ or ‘my B-drive is accepting that the cat is on the mat’ will suffice to replace any reference to mental states. As Eddy Zemach kindly points out, doing so deprives us of any reason to think the reduced statements are true. If one asks, ‘what makes you think your C-fibres are firing,’ what else could the asserter say apart from, ‘well I feel pain’? Same for the B-drive. Hence, one might replace all our mentalistic statements,…

-

-

Not Ready to Quit: Combatting Epistemic Apathy

For as many centuries as there has been a church, there has been a concerted effort to rationally defend its beliefs against skepticism. That’s what apologetics is supposed to do. A Christian apologetic is primarily a rational defense of the contents of the Faith. Throughout history, defenders of the Faith assumed that Christian beliefs aren’t mysterious inexplicable attitudes. They don’t arise from nowhere. Instead, they are properly formed. In our present age, although Christians have maintained their own psychological resilience in their beliefs, they are not so sure such resilience can be maintained in defending those beliefs. Some suggest that the most that we can do is help people see…

-

Beliefs and Imagination

The strength of my faith rests in part on repeated readings of the Chronicles of Narnia. The imagination is a powerful faculty of the human mind. As Gordon Graham writes, “Assembling evidence is often a rational strategy in arriving at a verdict, but imagination … can be another means by which reality is brought home to us” (Gordon Graham). What I want to consider in this post is the comparison Graham makes between imagination and a rational strategy. Presumably, by ‘reality is brought home to us’ and ‘arriving at a verdict’ Graham means belief. A ‘rational strategy’ for forming a belief (presumably) involves a proposition, p, being justified by evidence and basing…

-

On Intellectual Method

Broadly speaking, there are two competing intellectual methodologies: One either starts with the details, attempting to solve particular problems one at a time, or one starts at the top by attempting to develop maximally coherent systems. In a recent recent interview, James White said the following about his conversion to postmillenialism: “Postmillennialism is a top-down theology. It begins with over-arching themes that flow naturally and beautifully from Reformed theology. Instead of starting down at the bottom and trying to build up a system based upon interpreting symbols and apocryphal texts, postmillennialism starts with the over-arching purpose of God in Christ.” White starts with a system and then fits the details…

-

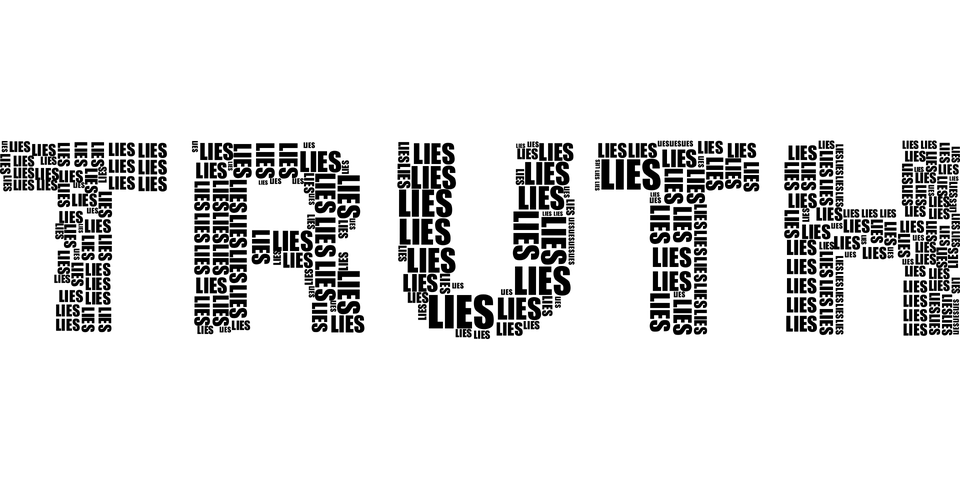

In Defense of Correspondence

I don’t know from where I got the following argument. I’m not even sure it’s any good. Here it is anyway. Some preamble: There are three broad theories of truth. According to a correspondence theory of truth, a statement is true if and only if it in some way corresponds to, or is in harmony with, a state of affairs. In contrast, a coherence theory suggests that a statement is true iff it does not contradict other statements which are part of a set of statements. Finally, according to a pragmatic theory of truth, statements are true when they are useful/beneficial when believed. Now, here’s the argument. Assume that the correspondence theory is…

-

Epistemic Pessimism

In a recent post, I described replacement epistemology, the project of replacing traditional questions such as justification for beliefs with psychology and sociology. Recently, I came across an article by Dr. Natalie Ashton, a philosopher at the University of Stirling who specializes in epistemology. The title of the article was “Why Twitter is (Epistemically) Better than Facebook.” But the article swaps epistemology for psychology. Consider the following paragraph: “Most of us know the tense, jarring feeling that comes with encountering a view very different than our own. In his book The Epistemology of Resistance, José Medina calls this feeling epistemic friction, because while it’s challenging, it can also be productive. Rub your…

-

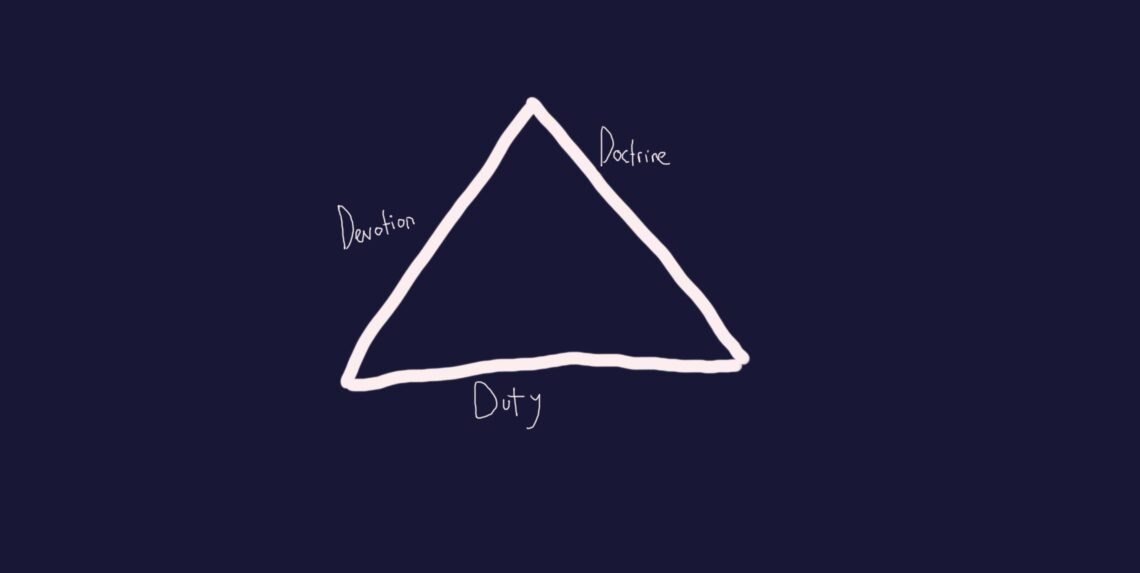

Doctrine, Devotion, and Duty

If I say, “I know God,” I am telling you that I am personally acquainted with him. If I say, “I know that God is omnipotent,” I am telling you that I have good reason to believe that the proposition expressed in that sentence is true. If I say, “I am obeying the command to love God by obeying his command to serve others,” I am telling you something about my activities. I am telling you about an obligation to perform an action and the fact that I am meeting it. All three of these aspects relate to one another in crucial ways. For example, I can’t have a personal…

-

Inference and Obligation

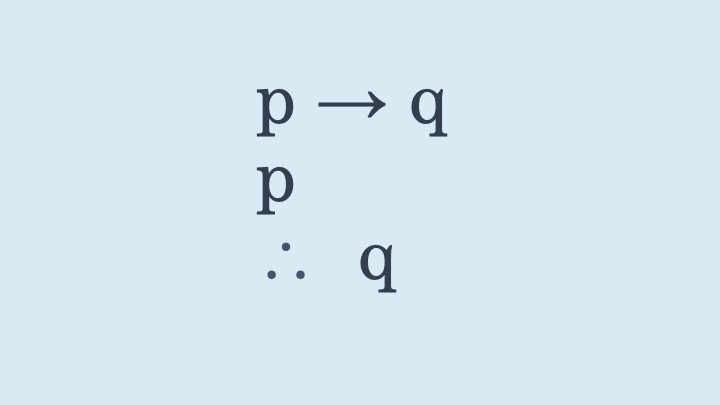

An inference is a kind of intellectual movement. Suppose I consider one belief I might have. I consider what follows from it and, as a result, I come to believe something else. Coming to believe something from something else is an inferential process. Most plausibly, the process involves adhering to a rule of inference. For example, the rule of modus ponens has the following form: if p, then q. p. Therefore, q. If I believe that apples grow on trees and I believe that the fruit I am eating is an apple, I can use modus ponens to infer that the fruit I am eating grew on a tree. The…