In a recent post, I described replacement epistemology, the project of replacing traditional questions such as justification for beliefs with psychology and sociology. Recently, I came across an article by Dr. Natalie Ashton, a philosopher at the University of Stirling who specializes in epistemology. The title of the article was “Why Twitter is (Epistemically) Better than Facebook.” But the article swaps epistemology for psychology. Consider the following paragraph:

“Most of us know the tense, jarring feeling that comes with encountering a view very different than our own. In his book The Epistemology of Resistance, José Medina calls this feeling epistemic friction, because while it’s challenging, it can also be productive. Rub your hands together and you’ll feel resistance. Do it for long enough and you’ll produce heat. Likewise, Medina thinks if we respond to other viewpoints in the right way we can produce understanding of the viewpoints we encounter, and of our own in comparison.”

Natalie Ashton

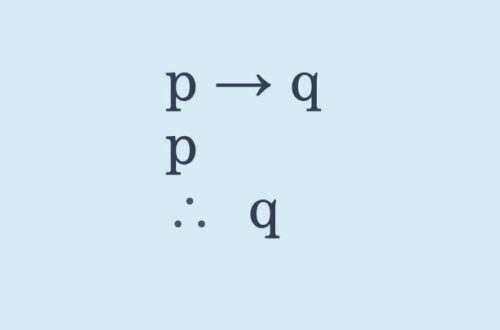

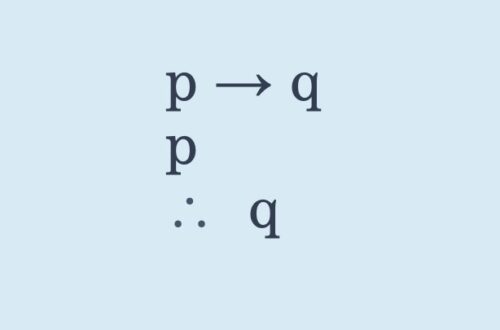

The way to spot the difference between psychology and epistemology, is that psychology tells you about the causal relationship between mental states, beliefs being a kind of mental state. It doesn’t tell you anything normative about the relationship between beliefs.

Instead, we are told that we should manage our beliefs in such a way as to avoid or alleviate friction. Dr. Ashton goes on to offer advice about what to do in circumstances in which we experience epistemic friction. She tells us “we need to acknowledge and engage with the different cognitive influences on our beliefs” by “becoming aware of external influences on our beliefs … sincerely and critically reflecting on these influences.”

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with what Dr. Ashton says. It is good advice. But there is something deeply pessimistic in thinking that all we can do is try to manage our beliefs sincerely. She rightly advises that “we should try to strike a balance between habitual (or stubborn) adherence to pre-existing beliefs and uncritical acceptance of what others say.” But that’s where the advice ends. She doesn’t tell us about how to judge which beliefs are true.

It is telling for a philosopher who includes the term ‘epistemology’ in her article that she does not go further to tell us how to discern what’s true from what’s false. Perhaps she would if asked. Nonetheless, the reluctance of many to engage in the traditional task of epistemology is indicative of a growing assumption that the task is useless.

Perhaps useless is a bit strong. Perhaps, instead, it is not normative. Indeed, this is the assertion of many proponents of our new cultural age. There is no one universal rationality, no set of universally binding principles for how we ought to manage our beliefs. There is just management. The only discussion taking place is whether managing our beliefs is going to be peaceful or violent.

The best we can do in such a situation is manage our beliefs in a way that involves the least conflict with others and the least internal angst. Hence, as far as adopting epistemic principles aids one’s peace, one is right to adopt them.

All this is very dour. What I’d like to suggest is that the demise of epistemology is not in fact as advertised. The pessimists are wrong.

First, there is no reason to suppose that we cannot manage our beliefs rationally. Skepticism of this sort is unsubstantiated.

But even if we accept such a skeptical view, the project of peaceful belief management is a hopeless one. Very few people will go along with a change in belief just to keep the peace. Sure, they might not speak up. But they won’t choose their beliefs on the basis of what will keep the most people happy or avoid internal angst. That’s not how belief works.

For one thing, beliefs aren’t chosen in the same way one chooses what to have for lunch. I come to believe something through reasoning. I don’t get much of a say in most of what those beliefs end up being. If I walk outside and get soaked, I can’t do much about my belief that it’s raining.

Further, beliefs don’t serve the purpose of peaceful management. The goal of believing what is true is far too strong to squash just to maintain a cohesive atmosphere. If I have a choice over believing something I have good reasons to believe and believing something that will produce the least harm, I am going to go with what is most reasonable. Why? Because the purpose of my mental state–belief–is to believe what’s true not what is most comfortable.

Someone might suggest that we choose comfortable beliefs all the time. But those in self-denial aren’t comfortable. They are in a state of cognitive dissonance and that’s bad psychology as I’m sure Dr. Ashton would tell us.

Hence, even if traditional epistemic questions about truth, justification and alike are unanswerable, the alternative holds out a goal that is eminently unachievable.