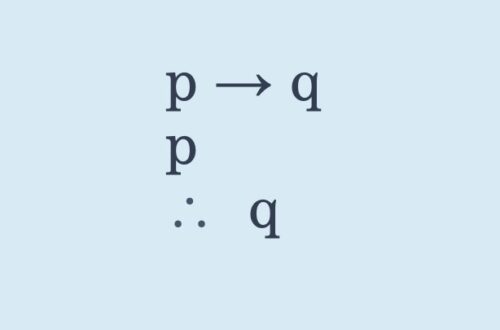

Broadly speaking, there are two competing intellectual methodologies: One either starts with the details, attempting to solve particular problems one at a time, or one starts at the top by attempting to develop maximally coherent systems.

In a recent recent interview, James White said the following about his conversion to postmillenialism:

“Postmillennialism is a top-down theology. It begins with over-arching themes that flow naturally and beautifully from Reformed theology. Instead of starting down at the bottom and trying to build up a system based upon interpreting symbols and apocryphal texts, postmillennialism starts with the over-arching purpose of God in Christ.”

White starts with a system and then fits the details into it. Presumably, he thinks starting at the bottom and piecing together the details won’t achieve the right result. Generally speaking, those who adopt the systems-first approach are seeking a maximally coherent system. Perhaps White thinks that starting with the details prevents a final system emerging. There are just too many opportunities for inconsistencies.

I used to be very much a systems-first kind of thinker. I liked developing a taxonomy of systems and adopting the one that seemed the most coherent and in line with what I already believed in other domains. I assumed that one view would be a natural fit with my overall worldview.

At the moment, I am teaching a class on Christianity, Culture, and the Arts. Much of the content is derived from the second-order discipline of the philosophy of art. The domain is fairly new to me and I have very much enjoyed starting a research project almost from scratch. I have also noticed a nagging pressure to adopt a grand system into which all the pieces fit. As anyone who has studied the topic will know, philosophy of art is a fiendishly difficult domain to systematize. As soon as one thinks one has some overarching system, there is a detail that won’t fit. As a result, I have become content to live with numerous tensions and questions.

Well, why not a system? What makes me resistant to adopting one in my class and in other domains? Here are some reasons for my rejection of a systems-first approach and why I have come to adopt a details-first approach.

First, a systems-first approaches have a tendency to skim details for the sake of of maintaining the coherence of a system. As Paul Boghossian writes,

“The ‘systems first’ approach inevitably leads to procrustean maneuvers in which we are forced to chop off crucial aspects of common sense … in order to make the phenomena fit our preconceived picture” (Paul Boghossian, “Closing Reflections,” in Debating the A Priori, 246).

I must admit, it is annoying to find that one conclusion on one detail won’t quite fit with other conclusions on other details. It is tempting to iron out the problem, making it fit with the system. But it is better to live with a degree of tension if maintaining a system entails ignoring data, or going against common sense.

Part of the problem for me was that I desired higher degrees of certainty than could be reasonably expected. However, intellectual work requires the rational management of one’s beliefs. It doesn’t require that one is equally certain that all of them are true. Some beliefs have a high degree of support, others not so much. Consequently, I began to consider it more valuable to have good reasons for my beliefs even if some of them don’t quite fit with each other. At some point, perhaps there will be an ironing out, but it will be based on evidence mounted over time. And in the meantime, I will have to be unsure of what I believe about some things. And that’s okay.

Second, as one becomes accustomed to a systems-first approach, it becomes more difficult to focus on the details. One not only wants maximal coherence, but also maximal generality. This problem emerges not only in the development of a system but also in dialectic with others.

It is too easy to categorize people as adhering to a whole system based on a few pieces of data. For example, I have heard (seen on twitter) people accuse others of being marxists based on a couple of sentences that sound like something a marxist might say. As soon as a system’s title has been introduced, neither side will debate the details. Instead, the battle of ideas becomes a broad-based battle of worldviews.

In our current cultural climate, this kind of systems-first, worldview discourse holds sway. It is a battle of theists verses naturalists, marxists verses liberals, progressives verses conservatives, fundamentalists verses liberals. But instead of debating the issues one by one in piecemeal fashion, entire systems are defended and attacked all at once.

The problem with such an all-or-nothing approach is that people who use it often conflate the consistency of a system with the consistency of people. While (idealized) systems may be internally consistent, people are not. People hold beliefs in one domain that are inconsistent with their beliefs in other domains. Worldviews are far too complicated to thoroughly work through all the details. Even those people with lots of time to think about it, can’t develop airtight consistent systems of thought. Consequently, assuming the consistency of a person’s worldview often leads to misrepresenting their view or attacking them for something they do not believe.

As I watch, I am afraid that arguing over entire systems all at once is a fruitless intellectual endeavor. Wars of ideas are usually won in the same way military wars are won, one battle at a time. They aren’t won all at once.

Even when a detail is apparent, a systems-first approach will often elevate a detail to the status of system. As Oxford prof, John Tasioulas writes,

“conceptual overreach … occurs when a particular concept undergoes a process of expansion or inflation in which it absorbs ideas and demands that are foreign to it. In its most extreme manifestation, conceptual overreach morphs into a totalising ‘all in one’ dogma. A single concept – say, human rights or the rule of law – is taken to offer a comprehensive political ideology, as opposed to picking out one among many elements upon which our political thinking needs to draw and hold in balance when arriving at justified responses to the problems of our time. Of course, we’ll always need some very general concepts to refer to vast domains of value – the ideas of ethics, justice and morality, for example, have traditionally served this function. The problem is when there is a systematic trend for more specific concepts of value to aspire to the same level of generality.”

I hope this trend reverses. If not, even when a substantive conversation or debate is about to take place, it will transmogrify into another war of systems.

A friend recently asked me what I’d like to see happen in our cultural discourse. I said I’d like to see more substantive debate. What I meant was, I’d like to see people argue for individual beliefs (the details) rather than arguing for the title of a set of beliefs. Arguing for or against an entire worldview all at once doesn’t allow for working through all its components. Yet a system’s components are its substance, what it is made of.

Having a details-first approach is, I think, more fruitful for our intellectual project. The details-first approach allows for an open minded inquiry into a particular domain. One can evaluate various theories and positions without having to check one’s system. The solutions are usually more likely to be true, or at least unbiased by one’s other commitments in other domains. They might not be grand, sweeping, or otherwise very dramatic. But that’s okay. Getting one small thing right is better than getting a thousand things to fit together.