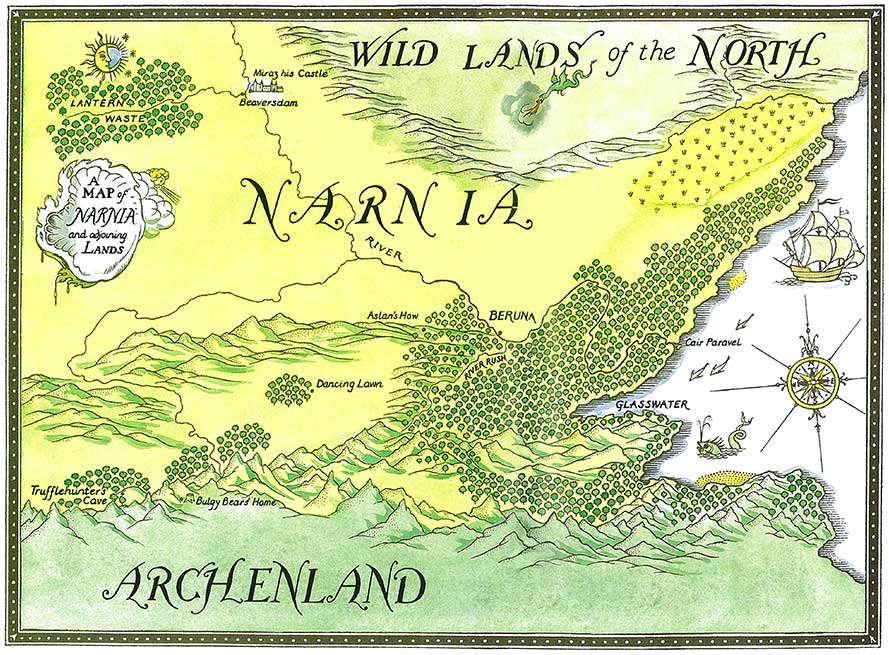

The strength of my faith rests in part on repeated readings of the Chronicles of Narnia. The imagination is a powerful faculty of the human mind. As Gordon Graham writes,

“Assembling evidence is often a rational strategy in arriving at a verdict, but imagination … can be another means by which reality is brought home to us” (Gordon Graham).

What I want to consider in this post is the comparison Graham makes between imagination and a rational strategy.

Presumably, by ‘reality is brought home to us’ and ‘arriving at a verdict’ Graham means belief. A ‘rational strategy’ for forming a belief (presumably) involves a proposition, p, being justified by evidence and basing one’s belief in p on the evidence for p.

What would the imaginative equivalent of ‘assembling evidence’ be?

Imagination is like belief in that both can have the same content, and both are mental states towards that content. Compare the following:

S imagines p

S believes p

But belief and imagination are two different attitudes toward propositions. Here is one difference: S believes p if and only if S thinks p is true. Not so imagination. S imagines p does not entail (nor is it entailed by) S thinking p is true. Belief is aimed at truth. Imagination is not.

Further, imagination involves an act of the will. I choose to imagine myself on a yacht. I don’t choose to believe that I am sitting in my chair at home writing this sentence.

Are they similar with respect to justifying a belief (serving as reasons to think a belief is true)? Graham says that there are two ways to form a belief, a rational way and an imaginative way. What might the two ways amount to? If they are both supposed to serve to justify beliefs, then we need some argument to show that to be so. Compare the following.

(R): S believes p because S believes ‘q’ and believes ‘if q, then p.’

(I): S believes p because S imagines ‘q’ and believes ‘if q, then p.’

The top one is a rational strategy. The bottom is a possible imaginative strategy. Here is one kind of example of the latter to consider (Berys Gaut gives many of these kind of examples):

(C1): S believes that she is courageous because S imagines being courageous in a battle and, as a result, believes that if she was in a battle, she would lead a charge at the enemy.

Does S’s imagination serve as evidence for her belief that she is courageous? It is difficult to say. I’m inclined to think that it doesn’t. I have frequently imagined myself being courageous in battle. But it doesn’t provide me with reasons to think I would be courageous in battle. Indeed, I could mount a pretty good case for believing that I would be anything but. Compare C1 with:

(C2): S believes that she is not courageous and S imagines being courageous in a battle but does not believe that if she was in a battle, she would lead a charge at the enemy.

Both C1 and C2 are possible (indeed, as I have confessed, C2 is actual in my case). Is there any reason to criticize either C1 or C2? I can’t see what would make either subject to any criticism. It is perfectly possible that two people differ with respect to their beliefs about how courageous they are and yet both can imagine themselves being courageous in battle. Hence, imagining, at least in this case, won’t have any purchase on the epistemic status of their beliefs. If generalizable, imagination won’t serve as fodder for propositional justification.

Neither is it the case that S is doing anything wrong in either C1 or C2. If C1 obtains and S comes to believe that she is courageous as a result of her imaginings, then she has not made some kind of mistake. She has been persuaded by her imaginings but being persuaded is not the same as being justified.

Consider another example.

Suppose that Jim wants to throw a party for his wife. He asks a friend to hold it at his home so he can set up without his wife seeing. The day comes, and the guests gather in the friend’s house. Jim notices that there are two ways into the house, both equidistant from where his wife will park the car. To get the guests in the appropriate place, Jim must discern which door his wife will choose. To do so, Jim must imagine his wife getting out of the car and walking toward the house. He can even imagine being his wife, seeing everything from her point of view. During his imaginings, Jim forms the belief that his wife will come to the door on the left. When she arrives, she does as Jim predicts.

Notice that nothing Jim uses for his belief formation is new information. Instead, all of it relies on beliefs Jim already possesses. Compare J1 and J2.

(J1): Jim believes his wife will enter through the door on the left because Jim believes his wife will prefer to walk past the lavender and will perceive the left door to be easier to get to.

(J2): Jim believes his wife will enter through the door on the left because Jim imagines his wife walking past the lavender and perceiving that the door on the left will be easier to get to.

Imagination, in this case, doesn’t tell Jim anything he doesn’t already know through perception and knowledge of his wife. He already knows that his wife likes lavender. He perceives that lavender is planted on the approach to the door on the left. He also perceives that the door on the left appears closer. Jim’s imaginative process doesn’t tell Jim anything. It doesn’t provide evidence. It only serves to connect beliefs in an appropriate way to produce a further belief that Jim’s wife will enter the door on the left. Hence, imagination cannot serve as justification for the proposition that his wife will enter the door on the left.

Consider another example.

(H1) S believes that she would like to live in this house because S imagines sitting having breakfast in the kitchen with the sun coming through the window and, as a result, believes that she would like to do so regularly (i.e. while living in the house).

Does the imagination serve as evidence for S’s belief that she would like the house? Again, it is difficult to say. It sounds like evidence. If I engaged S in an argument over whether she would like the house, it wouldn’t be odd for her to appeal to her imagination. Isn’t that just the way we choose houses? We see (imagine) ourselves living in the house and then form beliefs about how we would feel.

On the other hand, we are not forming those beliefs based on justified beliefs. Surely for anything to count as evidence, it must be at least justified. Consider the following.

(H2): S believes that there are men coming to steal her car because she can imagine that there are lots of burglars living in her area and forms the belief that some of them are going to rob her.

We wouldn’t count S’s imagined scenario as evidence for her belief. We would call her paranoid. She has no evidence for her belief that there are burglars coming to steal from her.

So, what is the difference between H1 and H2? Both involve S forming a belief as a result of imagining something that is false. However, we are likely to treat imaginings in H1 as evidence but not in H2. The answer, I think lies in what is being believed in H1 and H2. In H1, S comes to believe that she would like to live in the house. She has access to her preferences. As she looks around the house, she imagines living in it and comes to like the house. In doing so, she discovers that she likes the house. But discovery is not justification.

Why not? In my view, my preferences don’t come with justifiers. My preference for vanilla ice cream is just not the kind of takes justification. It might take explanation in terms of the qualities I like about vanilla ice cream, but I am not thereby presenting evidence for the case that I like it. On the other hand, my belief that my wife likes Moose Tracks does come with justifications. If she buys it and eats it whenever we have ice cream, I have evidence for my belief about her preference. But not so my own. If someone wants to argue over my preference, I could get some vanilla ice cream out and eat it. I could list the days on which I ate vanilla when there were other flavors available. But I wouldn’t appeal to my imagination to prove that I liked it. Imagination doesn’t gain any traction in the argument.

Graham invites us to consider an incident from the Bible in which David is confronted with his sin by the prophet, Nathan (if you are unfamiliar with the story, you can read it here). In the scene, David comes to believe that he has done something wrong because he imagines someone else doing something similar. He believes that the person in the story has done something wrong and that, if that person has done something wrong, so has he.

But now ask what belief needs justification and what would justify it. There are two candidates: (i) David has done something wrong (ii) it is wrong to perform the kinds of actions David has performed.

Are either of those beliefs justified by the story? Take (ii). David’s actions are wrong. What justifies this claim? One must appeal to a principle of ethics such as respect for persons because they are valuable or keeping a promise because truth is valuable. Can principles be established by a story? It is unlikely to be so. Principles such as these are based on metaphysics not on narrative.

To see this, consider a world in which there are only two agents. They have no history. Justifying their beliefs about ethics is not first a matter of narrative but metaphysics. Here are a couple of beliefs that they may have to justify in order to believe that the world in which they inhabit is one in which there is ethics: agents possess free will, agents have intrinsic value. Neither of these beliefs need be established by imaginings nor can they be justified by imagining anything. Those beliefs must be justified by something that is true of the actual world.

All that is not to say that stories play no part. Imagined scenarios often help in moral reflection. Considering whether some action is good or bad often requires that one tell a fictional story in order to come to a judgment on the matter. However, the story can’t serve as evidence for a moral principle. A story is data to be explained, not evidence to be presented. It serves to highlight important features of a moral life. But it doesn’t tell us what makes those principles the right principles.

(i) is also not evidenced by the story. Suppose David doesn’t see it. Suppose he tells Nathan that he has not committed the alleged offenses. “Bath…who?” David asks. In response, Nathan won’t retell the story or even tell another story. He will have to supply evidence for the belief that David slept with Bathsheba and had her husband killed in battle. Nathan needs witnesses to facts for this task, not stories of fiction.

What the story of David and Nathan does tell us is that deliberation over one’s choices and values is often aided by fictional narratives. One uses fiction to assess the value of actions and their outcomes. What if … stories help us think through what actions we’d like to perform. However, the utility of such deliberative techniques is only extended as far as expectations are met when one actual performs the actions in question. Whether those deliberations are effective can only be assessed empirically (by asking whether the values expected are actualized in experience). I am doubtful of such success. We only know what things are like when we experience them. Relying on imagined experiences leads to a great deal of disappointment. Consequently, I tend to remain agnostic as to whether things will work out well or not. Maybe they will, maybe they won’t. But how I imagine things will feel won’t tell me either way.

Nonetheless, something has occurred to David. He forms the belief that he has done something wrong as a result of hearing the story. Surely, he has been given reason to think he has done something wrong. But that’s not the only (nor the most plausible) explanation. It is more plausible that David knows that doing those sorts of things is wrong. He also knows that he has slept with Bathsheba and had her husband killed. What occurs is a proper connecting of those two pieces of knowledge such that a belief that he, David, has done something wrong. David already knows that actions of a certain kind are wrong and that he has performed the actions of sleeping with Bathsheba and having her husband killed. What he hasn’t done is realize that his actions belong to the kind of actions that are wrong. The story helps him make the connection. Moreover, once he has made the connection, he can properly base his belief that he has done something wrong on the belief that his actions are the kind of actions that are wrong (just like the character in Nathan’s story). However, the actual justification for his belief that he has done something wrong is not the story. The contents of the story are not part of the structure of David’s beliefs. Consider the components:

- Actions of type R are immoral actions

- David has performed actions B and C

- Actions B and C are of type R.

- Hence, David has performed immoral actions.

None of these beliefs are grounded in the story. David immediately recognizes the type of action in Nathan’s story as being immoral. The story is not trying to present evidence that they are wrong.

During the course of hearing the story, David realizes that he, David, has performed actions that fall under the same sort of action in the story. Again, the story doesn’t give evidence to that effect. Nathan tells David that David’s actions are the same kind as the actions of the character in the story, but the story doesn’t build a case for the similarity. David is just supposed to see the similarity. He does. And the story achieves its end.

David forms a belief (that he has done wrong). David is justified in his belief. His belief has a high degree of epistemic support. But the story does not serve as evidence for the truth of his belief.

Another way to think about it is to consider whether David obtains new information about his case. He certainly forms a new judgment about his actions, but he does acquire new beliefs about the world. He doesn’t discover some fact about Bathsheba, Uriah, or any event that has occurred. Instead, he comes to form a moral judgement on the facts that he already knows. Hence, the story doesn’t provide David with any justification for his belief even though it aids him in forming that belief.