In the early part of the twentieth century, a crisis took place in the art world. Objects that were not beautiful were hung in galleries as art. Most famously, in 1917, Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) submitted a urinal to an exhibition in New York. His piece was called “Fountain” (1917). If that could be considered art, then surely anything can be. The art crisis provoked questions. What counts as art? What is the nature of art? What makes it valuable?

Definition of Art

What kinds of objects count as art? Think of as many pieces of art as you can. You will probably come up with a list that includes things like paintings, music, drama, and literature. You might also include things like architecture, graphic design, pottery, or even cake design. We all have a rough idea of the kinds of things we generally count as being ‘art’. But what do those things all have in common? This question is very difficult to answer either because the answer seems to rule out things that obviously count as art or rule things in that obviously don’t.

The first, and most common answer, is that something is a piece of art if (and only if) it is beautiful. The problem is that there are things that are beautiful but not art (people, math) and things that are ugly that are (paintings deliberately depicting ugliness). Furthermore, it is not clear how to know whether something is beautiful. Is there some particular property of some objects, or is beauty ‘in the eye of the beholder’?

Other answers have similar problems. Perhaps something is art if and only if it causes pleasure. The problem with this answer is that there are other things that cause pleasure in a viewer but are not art (lectures, puppies). Some believe art is supposed to cause one to think, but again too many things would count as art.

In more recent years, people have looked to an elite group of experts to tell us if something is art. This group is called the ‘art world’. But the ‘art world’ leaves out too many things (folk art, arts and crafts, popular music) and includes things that most people don’t think of as art (Duchamp’s ‘fountain’!). Some people suggest that something is a work of art if and only if the person who creates it intends it to be a work of art. But this means anything a person makes can be art!

Perhaps, then, there is no good definition of art. However, since we all know what counts as art, we might merely say that works of art have a ‘family resemblance’ in the same way games resemble one another even though it is difficult to define ‘game’.

Nature of Art

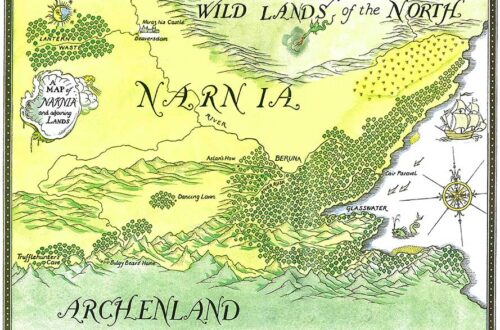

If we can’t give a precise definition of the term ‘art’, perhaps we will be better at determining its nature. What is art made of? It turns out that this question is not easy either. For example, perhaps you have a copy of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Many other people have copies of it as well. The copy you have is of the same novel that everyone else has. There is only one Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and it is not identical to one of its copies. So, where is it? If it is not identical to one of its copies, it cannot be a physical object. In fact, it cannot be located in space at all!

The Mona Lisa, on the other hand, is a physical object with identity conditions. Its copy is not the Mona Lisa. It is a forgery. Same for sculptures. However, what happens to a painting that is restored over time by other artists? Is there a point at which the original becomes a copy? If so, what is that point? One molecule of original paint? 50%? The answer is too vague in order to be precise.

Is a building like the sculpture or like a song? In some cultures, it is like the song. A building’s value is based solely on the architect’s design. In China, for example, a beautiful building that was first constructed hundreds of years ago can be completely reconstructed and be counted as the original building. However, the UN does not acknowledge it as a historical site despite its millions of annual visitors. The UN treats the building as the work of art, but the Chinese treat the design as the work of art and the buildings as its instances.

In sum, art is not one kind of thing. It may be a physical object, a pattern repeated in multiple instances, or a mental item in an artist’s mind.

Value of Art

Something about art makes it valuable. In fact, this is probably the first question we are presented with when we encounter any work of art: is it any good? So, what is it that makes art good or bad? In order to answer this question, it is worth considering the answers given throughout history.

The Classical Answer

The ancient and classical view was that art was valuable in so far as it imitated or represented reality (mimesis). For example, Plato thought that art should represent the ideal forms. Forms are unchanging non-physical things existing in another realm. They are like perfect patterns after which all other less perfect things are made. Since the realm of the forms is harmonious and rich, the value of art is determined by how well such harmony was imitated by the artist.

Similarly, Aristotle thought that beauty is a matter of objects having order and symmetry. But Aristotle didn’t think in terms of ideal forms. Instead, he was concerned with the proper function of concrete objects according to their kinds. If objects are arranged according to their nature, then they will be beautiful. Thus, when artists display representations of entities functioning properly, their works are beautiful.

Both Plato and Aristotle considered art to be a work that has a fundamental connection to what is real. Plato thought that art points up to the forms. Aristotle thought that art shows and aids the proper function of objects.

Classical Christian thinkers contended that the value of art relates to the intrinsic value of God. For example, Augustine argued that beauty in an object is derived from beauty in God. Therefore, art is valuable only insofar as it manifests the beauty of God. Thomas Aquinas thought that there was a deep connection between beauty and morality. Like Aristotle, Aquinas thought that goodness was determined by the proper function of objects, but also thought that everything ultimately ought to glorify God. Thus, he thought that the value of art could be determined by considering the orderly nature of the work and its heavenly purpose.

The Renaissance Answer

The classical view led artists to create heavenly focused works. Ancient sculptures were of ideal human beings. Spiritual entities were often the subject of paintings. Although Renaissance artists shared their forebears’ basic assumptions about the value of art, their subjects became more earthbound. The Renaissance is now considered to be one of the greatest eras for the production of valuable works of art. However, it was a time of transition. What followed from the Renaissance was the Modern and Postmodern eras. They were to take quite a different view on the value of art.

The Modern Answer

Up until the Modern era, people assumed that whatever it was that made a work of art valuable was in the work itself. However, during the Modern period, this assumption was doubted. For example, David Hume wrote, “Beauty is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.” In other words, what we mean by ‘good’ is just the positive response a work might receive.

The trouble with Hume’s view is that people disagree. How do we know which people to listen to about a work of art? Hume replied by saying that some people observe art in a better way than others. He developed the idea of the ideal art critic. To be a good critic, the critic should notice the details of a work, practice his critical skills regularly, have a wealth of experiences of artworks of many kinds, not let his personal prejudices affect his evaluations, and have a good awareness of what the work of art is attempting to say. Consequently, the evaluation of works of art in western society began to be governed by a group of experts.

Kant disagreed with Hume. In Critique of Judgment, he argued that judgment of beauty cannot be in us but must be in the world. But what? Kant argued that when one takes away the color and strokes of particular works, we can find the form of art. It is this that we find beautiful. However, unlike Plato, Kant thought that these forms are not known in themselves; they are mental interpretations of what we see. Thus, art is good only insofar as it fits the conceptual nature of the human mind. Some artists focus solely on the forms that appear to match the structure of the human mind. These works are often not of anything in the world. They are sometimes merely shapes or singular colors that are supposed to match the internal shape or hue of human visual systems.

The Romantic Answer

Though some artists attempted to express Kant’s ideas by conforming their work to merely the patterns of the mind, others thought that art can give us a glimmer of the reality beyond the phenomenal. But, in order to get at such a reality, the artist is required to express something beyond the rational. The artist must capture an emotional, mysterious level of consciousness in his work. In paintings, the romantics expressed the mystery by displaying scenes with glimmers of light from beyond. In music, they wrote pieces that were highly evocative of one’s emotions. Rachmaninov’s romantic compositions were filled with over the top emotional crescendos. The romantics expressed deep emotions through their art and taught to elicit similar emotions from those who experienced their art.

The Postmodern Answer

Postmodern art begins with the ideas of Nietzsche. Indeed, although people consider Nietzsche to be a philosopher, Nietzsche thought of himself primarily as an artist. His view of art reflects his general outlook on life. In The Birth of Tragedy, he portrays the world as chaotic and ultimately tragic. Life has no meaning; it is ultimately pointless. However, instead of despair, Nietzsche argued that that culture can thrive. How? Nietzsche argued that art saves us from being in despair by offering an illusion of meaning keeping us from confronting the meaninglessness of reality.

In our postmodern context, other answers to the question of what makes art valuable are as fragmented as our culture. Marxists believe art has value only insofar as it advances their vision for revolution and a resulting classless society. Conceptual artists attempt to deconstruct preconceptions of art. We have all kinds of reactionary art from punk art to comic books. It is difficult to discern any coherent pattern in postmodern art. All of it, however, is attempting to radically break with the idea that there are any governing norms determining the value of a work.

Christian Art and a Christian Worldview

How Should Christians Evaluate Art? Francis Schaeffer argued that the human ability to create is a good thing but, due to the fall, what human beings make make does not necessarily have value. However, he argued that Christians should be able to evaluate using a few simple standards of judgment:

- Technical excellence: In painting, for example, consider color, form, balance, texture of paint, handling of lines, unity of the canvas, etc.

- Validity: Is the artist honest to himself and to his worldview? Or does he sell out for money?

- Content: The artist’s worldview must be viewed in context of Scripture. An artist may not be aware of how his worldview is being revealed through his art. When false beliefs are disseminated through great art, the result is all the more destructive.

- Integration of content and vehicle: Great art is able to correlate content and style.

Schaeffer’s view is quite broad and allows Christians to evaluate a wide range of works of differing genres and styles.

In practice, Christians often evaluate art in connection with the culture that produces it. Art informs us about that culture, good or bad. According to Pastor John MacArthur, art always follows culture in whatever way it is going. Along with many Christians, MacArthur does not like the direction in which contemporary culture is going: “Music in our day is dominated by the rapidly degenerating corruption of our society. It is riding the culture’s corruption down.” For good music, MacArthur argues, Christians must find (and create?) good cultures.

The idea that art ‘rides’ culture in this way is a useful way to think about art. Art has a axiological dimension – it represents what people value.

Writer and pastor, Doug Wilson is decidedly negative about modern art for the same reason. He writes, “our culture is a diseased ulcerated boil of subjectivism and relativism, and modern art is the scab.” He argues that there is an objective standard for good art, the nature of God. The test for good art is whether God would like it: “the test for every aesthetic endeavor should be this: does God like it?…If not, then I shouldn’t either. If He does, then I may throw myself into lawful appreciation.”

One might wonder how anyone can know whether God would like a work of art. Wilson argues that we can know what God likes by studying God’s “aesthetic accomplishments” as found “in nature, and as represented in His artistry in Scripture.” Wilson’s main contention is that art that God likes is not subjective. It isn’t merely an expression of what’s in our heads. It should attempt to express what is objectively real and known through God’s revelation in scripture and in nature.

What kinds of art should Christians produce?

How should Christians approach creating art? Where should we begin?

Hans Rookmaker sees a broad purpose for the Christian artist: “To be a Christian artist means that one’s particular calling is to use one’s talents to the glory of God, as an act of love towards God, and as a loving service to our fellowmen.” Accordingly, Christian artists shouldn’t be motivated by selfish gain. It is hard to miss the egos of many artists, but Christians should at least not be governed by pride. Instead, art serves God in worship and others in love.

This is a good start, but what does this look like in practice? What kind of art should we make and where should we look for inspiration?

One way to approach this question is to consider art as an expression of a culture. If it is an expression of a culture, then we have to decide whether we should adopt or oppose the culture in which we find ourselves. John MacArthur argues that we should be deliberately different to the culture in which we find ourselves:

Music of the redeemed displays elements of beauty, elements of loftiness, elements of majesty, elements of order and design consistent with God’s nature. It is intelligent; it is systematic; it is sequential. It is poetic; it is harmonic; it is rhythmic. It possesses resolution. That’s our music. And since our Bible is timeless and divine truth is timeless, there’s a timelessness about our music – or at least there should be in the church. It is amazing how eager churches are today to adapt the music of the culture and try to sanitize it.

The view opposed to MacArthur’s suggests that we should appropriate the cultural artifacts of whatever culture in which we find ourselves. To appropriate a culture is to ‘take it as one’s own’ or to make use of some artifact from another culture and give it new context or use it for the purpose of perpetuating one’s own culture. In contemporary Christian circles we appropriate various popular culture motifs and re-work them in order to perpetuate a Christian worldview. In the 1980s, T-shirts of Heavy Metal bands were re-imagined in order to promote Christian ideas – Slayer became Slain; Megadeth became Megalife etc. In our days, church music often appropriates the latest trends of our culture.

I don’t have a solution to the dilemma – I’m torn between my principles (I agree that art should reflect God’s orderly nature) and my preferences (I love the blues and the ‘ordered chaos’ of great improvisation). Perhaps there is a case to be made for redeeming cultural artifacts. Perhaps that is not redemption but only capitulation. You and I have probably seen both and it’s not always obvious what it is that makes the difference. It probably has much to do with the heart of the person.

More recently, I came across an article by Christian philosopher, James Spiegel. He suggests a Christian artist should first consider his or her artistic character. Doing so will provide a prerequisite for making good art. Perhaps focusing on what kind of art we make is not the place to start. Instead, Christian artists should begin by focusing on the kind of artist doing the making.

Spiegel suggests five aesthetic virtues to develop and five aesthetic vices to avoid. The virtues include (i) technical excellence, the product of hard work developing the requisite skills, (ii) veracity, the truth and authenticity of the work, (iii) originality, involving constant effort to innovate, (iv) moral integrity, reflecting the artist’s commitment to biblical moral standards, and (v) intentionality, incorporating the artists considered reflection on his/her theory of art and art history. Vices include (i) laziness, being satisfied with poor technique, unoriginality, inauthenticity, (ii) banality, demonstrating a significant lack of imagination, (iii) artificiality, failing to take the artistic endeavor seriously, and (iv) utilitarianism, treating art only as a means to some other non-aesthetic end.

Working toward aesthetic virtues and away from vices should, if Spiegel is right, lead to creating good works of art whether a choral work or a blues riff all for the glory of the One who made all things well.

Bibliography

Aquinas, Thomas. Suma Theologica.n.d.

Gardner, Sebastian. “Aesthetics.” In Philosophy 1, by A. C. Grayling, 583-627. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Han, Byung-Chul. Aeon.2017. https://aeon.co/essays/why-in-china-and-japan-a-copy-is-just-as-good-as-an-original.

Hume, David. “Of the Standard of Taste.” 1757.

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Judgment.n.d.

MacArthur, John. Grace to You.n.d. https://www.gty.org/library/sermons-library/80-428/Is-Music-Worship.

Nietzsche, Fredrich. The Birth of Tragedy.n.d.

Plato. Symposium.n.d.

Rookmaker, Hans. Art Needs No Justification.1978.

Sheaffer, Francis. Art and the Bible.Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1973.

Spiegel, James. “Aesthetics and Worship.” The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology, 1998: 40-56.

Velasquez, Manuel. Philosophy.Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.