Mayer suggests that the now widely disseminated postmodern critique of modern methods of knowing–that the mind does not mirror reality, but always brings to bear presuppositions of language, culture and politics–can help faith-learning integration. According to Mayer, between the two extremes–modernist objectivism and postmodern constructivism–lies the role of faith.

Faith, for Mayer, is the human way of making sense of life, the world and experience in the context of an ultimate environment. Mayer suggests that such a definition is required to move beyond both existential leaps and authoritarian doctrine.

For Mayer, postmodern critiques of the modern project point to both a suspension of certainty and doubt. Both certainty and doubt, according to postmodernity, rest in modernist assumptions. Instead, Mayer argues, we need to be able to to achieve “functional certainties,” always open to revision, and “acceptable ambiguity,” a loose handedness when it comes to truth claims from either theology or other disciplines. Only thus will both disciplines “fit” together in the sense-making project:

All academic disciplines can contribute meaningfully to our sense-making, or faith. If theology was once the queen of the disciplines, it is today queen among the disciplines–regal because of its subject matter, but a human enterprise, nonetheless. Certainties of science or faith commitment must allow for continuous revision because there are always lingering ambiguities, mysteries, paradoxes, and antinomies to address.

An integration of faith and learning, according to a postmodern critique, is costly on both sides of the divide, but offers a religious solution, one that is epistemically humble yet able to transcend hegemonies on either side.

While Mayer diagnoses the problem well I am skeptical of his proposal for three reasons. First, how Mayer defines faith is difficult to square with how the Bible defines faith. The Bible is concerned with the content of faith–the whole hearted submission to the truth revealed to us by God, the gospel–and the commitment of faith–the entrusting of one’s whole life to Christ. Faith is given by God to human beings and follows an act of God in revelation (Rom 10:8) to specific people chosen according to God’s matchless grace. Mayer’s definition is simply too thin compared with what a Christian means by the term. Compare Mayer’s definition with Morris’ definition:

Faith means abandoning all trust in one’s own resources. Faith means casting oneself unreservedly on the mercy of God. Faith means laying hold on the promise of God in Christ, relying entirely on the unfinished work of Christ for salvation, and on the power of the indwelling Holy Spirit of God for daily strength. Faith implies complete reliance on God and full obedience to God

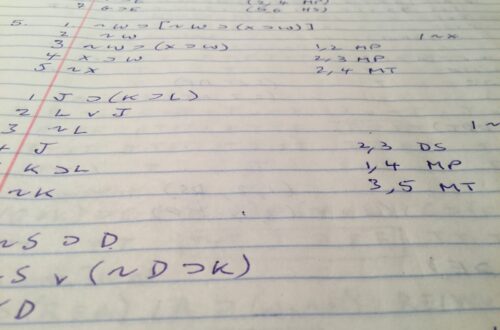

Second, it is not clear how Mayer avoids an ultimate skepticism. There simply is no “true truth.” This might be simply a rejection of modern epistemological commitments, but it is not only modernism that one would have to reject; the Bible assumes that human beings can come to certain knowledge, true beliefs warranted by God’s revelation: “Faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen” (Heb 11:1). Calvin’s definition of faith flies in the face of “functional certainties,” always open to revision, and “acceptable ambiguity”:

Now we possess a right definition of faith if we call it a firm and certain knowledge of God’s benevolence toward us, founded upon the truth of the freely given promise in Christ, both revealed to our minds and sealed upon our hearts through the Holy Spirit.

Certainty is not a modern idea. Surely we agree that modernism claimed a certain kind of certainty, one grounded in the authority of autonomous human reasoning, but there other ways to think about certainty. Biblical faith is one!

Finally, it appears that Mayer’s view of functional certainty, undeveloped in his essay, is open to the charge that it collapses into pragmatism. Does Mayer think, for example, that truth, in the correspondence sense, is unobtainable? If so, how “certainty” functions is by virtue of its ability to “make sense of life” not by virtue of its ability to get a grasp on reality.

Lanney Mayer “Integrating Faith with Learning in a Postmodern Age,” The Journal for Interdisciplinary Studies 23 (2011), 58-76.