In The Resurrection and Moral Order Oliver O’Donovan asks us to consider what we mean by love as a rule for life. Do we mean, on the one hand, that love is a summary and includes the rest of moral law? Or, on the other hand, do we mean that love is a priority over all other laws?

The latter involves responding to a moral dilemma by doing what is considered the most loving act even while an alternative action might be more justified on other grounds. The former may involve suggesting that a particular course of action is justified by a moral law and, though we might not like the result, is the most loving thing to do.

The priority approach leads to the problem of arbitrariness – it is not clear how we discern which option is the most loving and whether or not this or that option are loving at all. The inclusiveness approach suffers the problem of indefiniteness – if justice or prudence are merely forms of love we are left with the suspicion that those other moral obligations solely determine the form that love takes.

“Either we must regard love as an empty concept…to be filled with substantial content from the rest of law, or, in allowing that it has a content of its own which may overrule the rest of the law, we must make it the sole criterion by which we resolve every decision.” (Oliver O’Donovan, Resurrection and Moral Order, p.202)

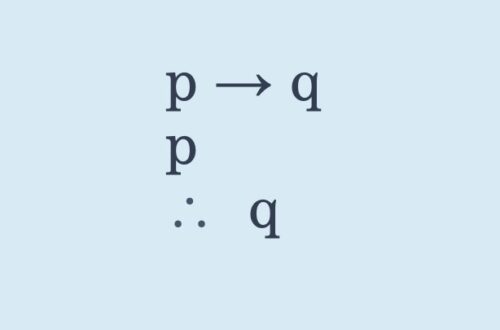

O’Donovan argues that the dilemma is false. To see this he asks us to consider what conceptual knowledge is presupposed in either position. If it really was the case that love trumps other moral laws then we would require a unifying and static principle of love which determines the choice we make. But this in turn relies upon our conceptual knowledge of other moral laws. He suggests that we are hard pressed to come up with any concept of love that makes no use of all our other moral obligations. The same is true from the other side. When we make the concept of love determinable by other moral obligations we are merely attempting to use other obligations to determine what love is.

O’Donovan argues that this implies a provisional kind of justice accompanied by a provisional knowledge. Consider our concept of love. What makes it complete, on O’Donovan’s view, is revealed in our experience of an event. What then determines the concept? Is it the event or the concept? If there is no a priori concept of love available then surely love remains undetermined until our experience is complete. If there is an a priori concept of love, how do we get at it?

For O’Donovan the Bible’s concept of love is revealed to us accompanied by the transformation of our worldview in accordance with its divine author. And since that divine author is also the creator of the world the concept we gain from scripture will be the right one for application to ethical dilemmas we confront in the world. O’Donovan tells us that reading the Bible illuminated by the Holy Spirit gives us access to the mind of God and God is love. As we know God and his love for us we know love. Knowledge of God as we encounter Christ in scripture and knowledge of love as we encounter the world he made are jointly sufficient for a knowledge of love.

O’Donovan has built a reputation for making us think about our presuppositions. However, his ethic avoids trying to prescribe what we should do in practice. His ethic is existential and is concerned with a personal knowledge of God as opposed to God’s commands. He is opposed to developing a compendium of dos and don’ts from scripture and sees our ethic derived from personal experience not from rules set out in list form. Whether to avoid poor casuistry or because he is concerned to answer a deeper question, O’Donovan’s avoidance of command theory is not necessary when one considers how God’s commands come about. God’s commands are a reflection of his divine nature. Why not, then, show how divine commands reflect God’s divine nature? Do we not know God’s nature through his commands and then know the goodness of his commands through obeying them?