God is never surprised by anything, never acquires knowledge and finds playing hide and seek quite dull. God has all the symptoms of omniscience. But how does God know what he knows? What counts as knowledge for God? Does he have justification for his beliefs? The following is a sketch of some options.

What exactly do we mean by omniscience? First, God’s omniscience, in a propositional sense (and let’s confine ourselves to propositions for simplicity’s sake), means that for every proposition p, if p is true, then God knows p. Entailed in this view is the further feature of omniscience such that for every proposition p, if p is false, then God knows that p is false.

Second, God’s knowledge is complete. There is no proposition that God does not know. If God lacked one proposition there would be no way to know if that one proposition would change the truth value of a proposition that he already believes. Because there is no way to guarantee that the unknown proposition would not falsify some, or even all, of the other propositions the possibility of such a propositions implies the possibility that God knows nothing at all.

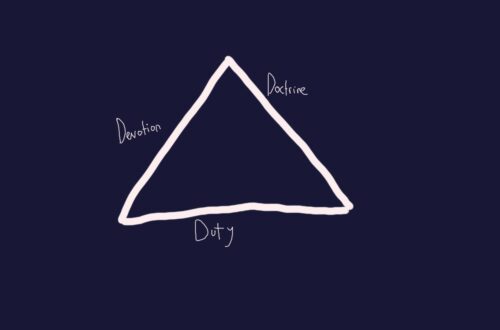

In order for God to have complete knowledge he must meet the maximum conditions for knowledge. Let us take a common view of human knowledge – justified, true belief. For God, the strictest conditions are in play. He must obtain maximal justification.

Some might suggest that God is maximally justified in the sense that he has the highest probability knowledge based on comprehensive evidence available to him. If God has all the evidence at his disposal then there is no further evidence available from which to cast doubt on what God believes. Further, there is no possible further evidence that would hold sway on what God believes.

Knowledge, on this view, is grounded in access to evidence. God has all the facts and, as a consequence, knows everything there is to know. However, this view comes into conflict with another attribute of God – aseity. God’s aseity refers to his independence. To say that God knows independently is to say that he knows without relying on any external factor. The evidential picture gives God access to all evidence, but the evidence in question is external to God and it appears that God is dependent on it for knowing it.

|

| “It’s elementary” |

Second, evidence that supports a belief enough to count as knowledge merely has to be over 50% sure. If God has evidence for p such that he is 50% confident then he has enough to know p. What, according to this view obliges God to have 100% confidence? If God is only required to be maximally justified in that sense he can know all things without all the confidence in his beliefs. This does not entail that God lacks anything, only that the standard seems to fall short of what we think of when we consider omniscience. God knows all things and has access to all the evidence, but does not need to be 100% certain of what he believes.

Perhaps, instead, God’s knowledge is somewhat akin to a coherence theory of truth. Belief is justified by its internal coherence. God’s beliefs are completely free of contradictions and inconsistencies. This view might suggest that God’s set of beliefs prior to creation include all logically possible beliefs.

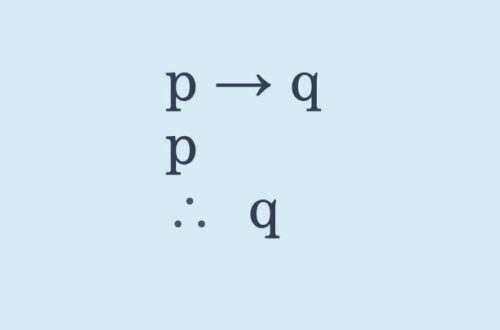

One possible problem with this view has to do with inference. Does God infer from one belief to another? Surely we agree that God is rational and that he follows the laws of logic. However, inference implies moving from one premise to another and then to a conclusion. Yet this seems to rub up against God’s immutability. If God were to infer from one premise to another, then it appears he grows in beliefs or, at the very least, has a sequence of thought. Even if this is very fast inference does not seem to be something that is instantaneous.

Why not? Mavrodes argues that just because we infer sequentially does not mean that God has to “move” from one premise to another and then form a conclusion. God, because of his perfection, could be able to draw all conclusions simultaneously with the premises.

A second problem with this view is that although there is no internal contradiction in God’s beliefs there is no guarantee that his beliefs will map exactly onto reality. One might suggest that God’s omnipotence overcomes this problem because he has the power to make his beliefs come true in reality. This misses the point of the objection, however, since the problem does not come about due to God’s inability to actualize a world of his choice, but whether or not God’s knowledge counts if it maps onto reality. However, coherence does not guarantee that God’s set of beliefs map perfectly onto reality, only that they do not contain a contradiction. If what makes his belief true is that there is no contradiction among those beliefs, then they do not have to map on to reality in order for them to be true.

God may well be justified in his beliefs because of a feature or two of his nature. If God is perfect in other areas might this not justify his beliefs enough to make them knowledge. Perhaps one such attribute is God’s goodness. Since God is morally perfect he cannot lie. To lie would be to breach his own perfection. Omnibenevolence refers to God’s intrinsic moral status. He is without sin; in him there is no darkness. The thought about how this feature connects with God’s ability to justify his beliefs relies on a strong sense of moral perfection. It is impossible for God to sin. To lie or to believe something false is a moral failure. Therefore, whatever God does know cannot be false because if it were God would believe a lie and therefore not be morally perfect.

|

| God cannot cheat. |

Another theory might ground God’s beliefs in his will. God’s freedom suggests that God’s choice, made independently of external factors, includes what God knows. God’s choice of what is true cannot be constrained by evidence of what is true. God both chooses what to believe and what he believes is true. It is true on the grounds that he has chosen it. This view holds that beliefs that God has are internally justified. There is no need for an external factor to provide justification for his beliefs.

This view has the problem of arbitrariness. If what God chooses to belief is in virtue of its being chosen by God true then there are no apparent limits to what God might have chosen to believe and, therefore, to be true. Consider 2+2=4. This truth is plausibly a necessary truth. However, on this view, 2+2=4 is true if God decides it to be true. If he could have chosen differently then it is not a necessary truth.

A possible line of response to this is to say that God could not believe something irrational and that, in turn, rationality is what God has inherently. His beliefs are always rational given his rational nature. John Frame says:

If human knowledge is dependent on God, then God’s own knowledge depends on God. That is, it is self-attesting, self-referential, and self-sufficient. His knowledge is the ultimate “justified, true belief.” He is the ultimate justification of knowledge, the standard for creaturely knowledge and his own knowledge. He is the ultimate truth: the truth is what he is and what he has decreed to be. And this justification and this truth are enclosed in God’s ultimate mind, ultimate subjectivity, ultimate belief. So, as many theologians have taught, God’s knowledge depends only on himself. God knows all things by knowing himself and knowing his plan for the universe.[1]

Frame’s view is that God is justified in his beliefs by his own nature and his will. By his comprehensive knowledge of himself and his will God is self-justified.

2+2=4 can be necessarily true and still be dependent on God. In every possible world in which there are quantities such as 2 and 4, 2, when added to 2, will always come out as 4. Perhaps it is possible that there be a world in which no creature recognizes number of entities and, consequently, is unaware of 2s and 4s, but if the creature had been aware of 2s and 4s 2+2 would equal 4. Furthermore, God would know that if he had created a world in which creatures were aware of 2s and 4s they would have been aware that 2+2=4. This is enough to say that 2+2=4 necessarily.

[1] John Frame, The Doctrine of God (Phillipsburg: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, 2002), 481.