Jason Lisle argues that we have a moral obligation to be logical: “Thinking rightly is not optional… It is something God requires of us.” His argument is as follows: To think logically is to think – in a sense – like God thinks. And, by definition, to be logical is to reason correctly. This makes sense when we consider that God always thinks correctly. God is the ultimate standard of correctness. So if you want to think about a particular topic correctly, you must think about it in the same basic way that God does. The argument depends on what it means to think about something ‘in the same basic…

-

-

A Silly Pro-Abort Argument

Having ‘moral status’ equates to being the kind of thing it is wrong to kill. According to Elizabeth Harman, if a woman decides to have an abortion, then the fetus does not have moral status. If the mother decides not to have an abortion, then, due to the future life of that fetus, the fetus has moral status. I have moral status. If my mother had decided to abort me, then I would not have had moral status. When I was a fetus, my mother decided not to abort me and, in virtue of that fact, I had a future life. Consequently, I had, and still have, moral status. This…

-

Logic and Normativity

As I argued the other day, there are some people who think reality is underwritten by various norms. I call them normativists. For example, a normativist will think that there are ethical principles that are objective, universally binding, and immutable. As I suggested, normativists will also think this about the rules of grammar – they are objective rules to be discovered not conventions to be created. Today I came across an article that suggests that the normativist is wrong about when it comes to logic: …logic has developed over a long time, and it is likely to continue developing. Currently, non-classical logic is working to fix some of the things that…

-

What’s Wrong With Mind-Reading Arguments

Consider Fred. Fred hates cars. But Fred hates cars in 1946. We don’t know why he hates cars and perhaps he might like modern cars. We can speculate all we like, but we can’t say for sure that Fred would like modern cars. We can’t say, “Well, when Fred hated cars in 1946, cars were very different. Fred didn’t even know about modern cars. Therefore, Fred would not hate cars in 2017.” The reason we can’t make the conclusion is because no kind of car was specified as the subject of Fred’s scorn. Indeed, it is highly likely that Fred hated all species of cars not because he hated every…

-

Why I Teach Logic to Children

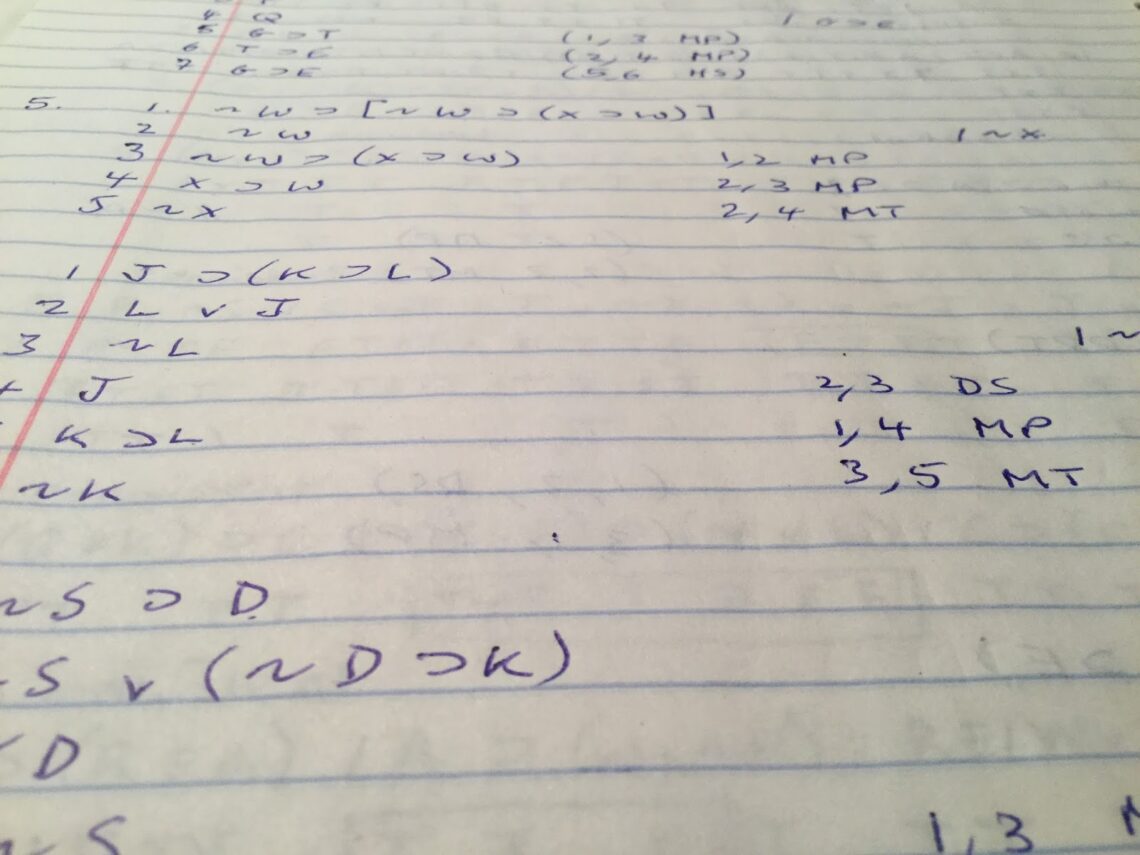

I teach formal logic to middle schoolers. This comes as a surprise to many people since formal logic is usually first encountered at college (if it is encountered at all). However, the more I teach logic, the more convinced I am that we should be teaching formal logic to our children especially during the middle school years. Not everyone agrees with me. Some suggest that formal logic is much too advanced for children of this age. Others suggest that logic is only important for certain subjects and not necessary for everyone to learn. Let’s start with the latter objection: why should everyone learn formal logic? Surely logic is useful for…

-

Blunting the Fallacy Fork

Marrten Boudry claims that there are far fewer fallacies out there than we think. His reason involves a ‘fallacy fork.’ The fallacy fork is a dilemma the conclusion of which is supposed to show us that fallacies are not usually fallacies. Here is the fork: Either the fallacy is hardly ever used, or it is hardly ever fallacious. For a fallacy to count, it must imply some deductive form. Since, we hardly ever make deductive arguments that are candidates for fallacies, we should prefer the second fork. So, are what we call fallacies not really fallacies after all? Consider, the ad hominem fallacy. A candidate for office claims that policy…

-

Disturbing Reasoning

Today I came across two examples of disturbing reasoning. I am distinguishing disturbing from merely fallacious. Disturbing reasoning deserves its own box, brand, and–ever hopefully–banishment. To reason disturbingly is to make an argument that implicitly accepts a disturbing assumption. A disturbing assumption is some belief that is almost universally rejected or should be rejected as immoral. Here is an example from Penn Jilette: The question I get asked by religious people all the time is, without God, what’s to stop me from raping all I want? And my answer is: I do rape all I want. And the amount I want is zero. And I do murder all I want, and the amount…

-

The Bottle-Kicker: Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for Beginners

Here is a kind of statement: If A, then C. The statement is called a hypothetical statement and it has two parts joined together by “if…,then…” In the statement above, A is called the Antecedent and C is called the Consequent. We use these kinds of statements all the time: “If I don’t get a move on, I’m going to be late” “If there’s milk in the fridge, then you can have it.” The antecedent is sometimes called the sufficient condition and the consequent is sometimes called the necessary condition. So, how does this kind of statement work in arguments and how can we understand what the difference between those…