|

| “Lock ’em up!” |

Punishment, in our culture, conjures up images of a Dickensian, authoritarian and bleak society, one marked by shouting and hitting. While there is no doubt that evil people use punishment as an excuse for cruelty, I’d like to suggest that punishment itself is morally justified. Much as I’d like a world without punishment, I don’t think we can have it if that same world has moral evil in it. So, I’d like to go against the grain: punishment is right, not always and not every kind and certainly not with hatred in the heart, but justified in a fundamental way. Actually, I’d like to go a tad further and suggest that punishment is a duty that obliges certain people in certain roles to carry out actions against wrong-doers and that punishment can harm or deprive wrong-doers in certain limited ways.

Just ask yourself this: when someone does something wrong, a criminal perhaps, or a naughty child, or a truant student, what is the right response? To some extent, the answer depends on what we mean by wrong. When someone mucks up we think it might just be a mistake, an oopsidaisy. But oopsidaisys don’t include murder, stealing, cheating and alike. Those are called evil or moral wrongs. They are intentional acts that go against a rule. I don’t mean they result in something that we don’t like. I know consequentialism is all the rage, something is only right or wrong because of the result it produces, but I think that’s a bad way to think about ethics. Rather, a wrong, as I am going to take it, is an act that breaks a rule. A rule implies an obligation a person has regardless of the outcome. So what duty does an authority, like a government or parent, have when someone under that authority does something wrong? That duty, I shall argue, is to punish the person for their wrong doing. Punishment is both a reasonable and theologically justified act that an appropriate authority has a duty to use against people who deserve it in order to restrain evil.

Just Deserts: Where does the idea of punishment come from? Louis Pojman argues that punishment follows from an intuitive truth. He calls it primordial meritocracy. Primordial meritocracy suggests, “every action in the universe has a fitting response in terms of creating a duty to punish or reward, and that response must be appropriate in measure to the original action.”[1] Pojman argues that this is an intuitive truth, something basic to how the world works. It seems that, on reflection, actions that are laudable deserve rewards and evil actions deserve punishment. The denial of such an assumption goes against our basic intuitions about how the world works. What would it mean to say that crimes warrant no punishment or that praiseworthy deeds are not at all praiseworthy? Indeed, to deny such a notion would be tantamount to denying the idea of merit in its most basic form. In other words, the denial of primordial meritocracy has a pretty high price. Given primordial meritocracy, then, “it follows that evil deeds must be followed by evil outcomes, exactly equal or in proportion to the vice or virtue in question.”[2]

Punishment is not revenge. One might think, then, that punishment is the same thing as revenge, a form of pay-back. But there is a distinction. To see this, consider the parents who know that it is good for their child to know that they have done wrong and to be punished so that they will be restrained from doing wrong in future. They, like many parents, often do not wish to carry out any punishment at all. There is no desire for revenge yet they punish anyway for the good of the child. And, given primordial meritocracy, they would be right to do so. Of course the reverse is often true. A parent may loose his or her temper and act in anger against the child. Now the anger may be a genuine anger against sin, but it may be an anger more akin to someone acting in vengeance. An act motivated by a desire to get back at a child is not the same as a punishment, which entails no such motivation. Christians are not permitted to act out of vengeance. As Peter writes, “all of you be harmonious, sympathetic, brotherly, kindhearted, and humble in spirit; not returning evil for evil or insult for insult, but giving a blessing instead” (1 Peter 3:8-9a), but they, if they are in certain positions of authority, are obliged to punish as we shall see.

Duty: Punishment is a duty that certain authorities are obliged to carry out. That might sound a little harsh. Notice though that it is a prima facie duty. That means it is a duty that is only actual if there are no other mitigating circumstances that would allow an authority not to act on their duty. There may be factors that determine whether or not the duty to punish becomes actual. Court cases are often focused on those factors rather than whether the accused committed the crime or not. However, if there are no mitigating circumstances, then the duty becomes actual and, in that case, the relevant authority ought to carry out a punishment.

Authority: Can anyone carry out a punishment? In a word, no. Punishment is not open to everyone to carry out and not every form of punishment is open to every kind of authority. There are three authorities the New Testament talks about: government, family, and the local church. In Romans 13 Paul makes the case that government has the legitimate authority to punish citizens for crime:

Every person is to be in subjection to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those which exist are established by God. Therefore whoever resists authority has opposed the ordinance of God; and they who have opposed will receive condemnation upon themselves. For rulers are not a cause of fear for good behavior, but for evil. Do you want to have no fear of authority? Do what is good and you will have praise from the same; for it is a minister of God to you for good. But if you do what is evil, be afraid; for it does not bear the sword for nothing; for it is a minister of God, an avenger who brings wrath on the one who practices evil. Therefore it is necessary to be in subjection, not only because of wrath, but also for conscience’ sake. For because of this you also pay taxes, for rulers are servants of God, devoting themselves to this very thing. Render to all what is due them: tax to whom tax is due; custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honor to whom honor (Romans 13:1-7)

The government has the right and the duty to mete out punishment on those who do evil. This is not mere human capriciousness, but a God-ordained means for justice. Citizens ideally should be able to point out flaws in a government’s practice, but they should not eschew the rightful authority of the government to enforce the law.

The Bible also gives the job of punishment to parents: “The rod and reproof give wisdom, but a child left to himself brings shame to his mother” (Prov 29:15). “If you strike him with the rod, you will save his soul from Sheol” (Prov 23:14). One might quibble with the form of punishment and seek something that does not involve spanking, but the principle is clear – parents should punish their children for wrongdoing. It is actually good for the child.

Notice that in each case the authority is granted to some people over some other people. Governments have authority over citizens of that country, parents over their children and local congregations over its members. Punishment is limited in kind and in availability.

Restraining Evil: Punishment is not mechanical in that it is not reducible to a function of reality like gravity, but has a purpose: to restrain evil. Paul describes government as God’s tool for restraining of human evil. He even wrote this during the reign of the horrible Nero! I wondered if this runs counter to God’s reluctance to punish. Isn’t God patient with us? Why then should we act differently to others? Of course, in some sense, we should be patient with one another, but when an evil is committed that warrants punishment appropriate authorities should not dilly dally. Here is one answer: It is perhaps because God is patient that he employs human authorities as instruments to restrain evil. If God was to act directly and immediately there would be no delay; he would come to judge right away. And when God comes to judge, his punishment will be swift, terrible and complete. But because of his mercy he delays his coming in judgment. Instead, he employs a human means to restrain our evil.

An implication is that if punishment is wrongly avoided then evil runs rampant. I must say, I don’t like the thought of being punished any more than I like meting it out. I’d far rather avoid the whole thing. But, on the whole, I am persuaded that punishment is a right action when carried out in the right way. But my inclination to delay when it is clearly the right thing to do is a sign of my own resistance to live rightly. Slowness to punish is, in other words, not necessarily a virtue. One should, however, be slow to anger. But anger is not necessary for punishment. In fact, wrongful anger, anger motivated by revenge, is never a good motivation for punishment.

Objections: Some believe that punishment is wrong because it degrades the innate dignity of a human being. Though he or she has acted wrongly, a criminal remains a human being and in virtue of that fact should be treated with dignity no matter what he or she has done. Punishment reduces or harms that innate dignity and therefore is wrong.

There are two responses to this line of thinking. First, there is a confusion of kinds of dignity involved here. It is true that all human beings have a dignity that cannot be removed. Christians believe that all people are made in the image of God and that warrants a certain treatment. It is why, for example, Christians oppose slavery, abortion and oppression. However, having that kind of dignity does not rule out being punished. Why? Consider another kind of dignity. A person who overcomes overwhelming odds and achieves something of high value obtains a kind of dignity most of us never achieve yet most of us are not any less human than a person like that. This suggests that certain acts of bravery etc. raise the dignity of a person over everyone else and we should treat them accordingly. People who achieve greatness deserve reward; they deserve our praise and, in some cases, material benefits. The same is true with evil acts. Though people who do evil are no less human, and so have the same innate dignity as the hero, they have acted in a way that makes them less dignified in another respect. Punishment in response to evil is no less warranted than the public praise and reward we give to people who achieve greatness. They have earned a punishment. The Bible says that the wages of sin is death (Rom 6:23). It is a payment warranted by an evil action. That person does not lose the first kind of dignity since it is not earned. In fact, that is why punishment should be carried out in a humane way seeking only to appropriate a harm that is warranted by the crime. It should not be a cruel and unusual punishment like torture, but an appropriate, proportiante punishment. (see Gilbert Meilander’s book, Neither Beast Nor God, for a discussion of the two kinds of dignity).

Second, think for a minute about dignity. Consider the rapist and his victim. The dignity that has been attacked, in this case, is the dignity of the victim. It is the innate kind of dignity that has been violated. The victim has been treated as if she were not made in the image of God. How should human dignity be valued? Of course, there are many things we can do for victims we know. We can slowly help them heal through loving acts towards them. But what should the government do? Anything? Some people, refusing the notion of harsh punishment, say that prison is appropriate, but only to secure the protection of the population not as a punitive measure against the criminal. But notice that this does nothing to value the dignity of the victim. Punishment, on the other hand, says that the dignity of the victim is valued. It sends a clear message: if you rape, and thereby devalue the dignity of the victim, the state will act harshly against you demonstrating the inherent value of the victim.

Some people think that punishment just raises the heat; it just elevates the tit-for-tat mentality of everyone involved. Punishing crimes, especially crimes that have no obvious, immediate effect on anyone else such as personal drug use, does more harm than good. Why not, instead, focus on educational programs or rehabilitation of criminals so they can remain in society rather than go to prison and possibly become more criminalized?

Let’s consider a slightly different objection. Imagine, if you will, a possible world in which wrong doers are always punished and yet the amount of evil in that world is equal to the amount of evil in another possible world in which no wrong doer is ever punished. It seems, given this possibility, that there is no use in punishment. It is too difficult to tell whether or not punishment has its desired effect. What you might be able to see is that to use this argument I have to be committed to a version of consequentialism, that an act is justified by the outcome of the action. Given that the outcome is neither here nor there, the action fails to be justified. However, consequentialism is false. Rather, actions are justified on other grounds apart from results. If there is a prima facie duty to punish a wrong doer for a wrong action and there is no mitigating factor that would restrain the relevant authority then the duty becomes actual and the authority should punish the wrong doer regardless of the outcome.

Now, let’s return to the original problem. If meting out punishment provides fuel to the fire, inflames a situation, is it right to carry it out or should one restrain? Consider an arrest of a person who is guilty and who is also a member of a minority group. The minority group are known for violent protest and even for killing people when they are enraged. Should the authorities take into account the probable outcome of the punishment? Should this count as a reason not to punish? The answer is: no. Although much should be done to reduce the risk of reprisals, if the punishment is deserved (the person in question must be found guilty and given due process) then it should be carried out.

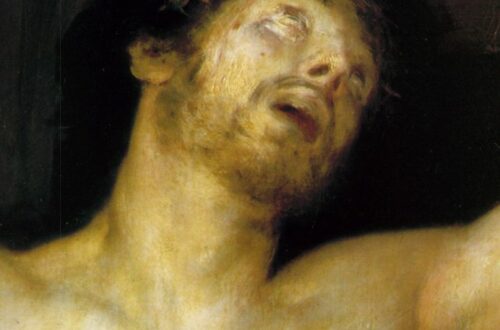

One last point: the gospel presupposes that divine punishment I was just mentioning. Jesus takes the punishment that human beings deserve. He bears our sin and is fully rewarded for it in his death. When we accept this gift we accept that Jesus took up our just deserts and applied it to himself. The appropriate authority, God the Father, metes out the punishment on his own Son, the punishment we deserve. To reject Christ is to accept on oneself a penalty for sin – one’s own eternal and unending punishment justly deserved by all human beings.

Can we overcome the results of a google image search, all those bad men beating on innocent people? It turns out we can only do this if we think we’re innocent. But surely we are not so naive. In any case, to make moral decisions based on whether or not we feel something good or bad about it is not a very good idea. Sometimes doing right feels bad, but feel-bad right actions are always better than feel-good wrong ones as any addict will tell you.

[1] Louis Pojman and Jeffery Reiman, The Death Penalty: For and Against (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc., 1998), 15.

[2] Ibid.