I said that, for my defense I would contend that God determines all things, including evil, while human beings, not God, remain responsible for evil. This claim rests on a view of providence commonly known as compatibilism. Compatibilism holds that determinism and human free will are compatible. I also explained that I consider what is evil to be determined by the character of God and his revealed moral law. Although an objector might not find either of these positions agreeable, neither is irrational.

The final, and most pressing, question that I am charged to respond to is what, even given what I have just said, would justify God in sustaining a world in which evil exists. In other words, I am provoked to give a possible reason that God does not remove evil. The reason, in order to pass the test for rationality, must be a morally sufficient reason. In my previous post I showed how John Feinberg offers a possible answer to this question. However, the following is a somewhat alternative answer relying not on what might be possible, but on the human epistemic condition we find ourselves in. It seems that for me to solve the problem of evil posed I may not be required to attend to this question.

Why? Well, it has to do with knowledge – how much we can know, how much God can know and how we come to know anything in the first place. In addition to believing that God exists I also believe that there are many things that, if one does believe that God exists, are unknown and can properly remain unknown. Therefore it is possible for me to say that I can neither suggest an explanation for God (since God is the explanation for everything else) nor can I know the mind of God (since what I know is limited and what God knows is comprehensive). What I can know about God is known because God gave me the capacity to know it and God reveals it to me. Consequently, all I am charged with producing is a theological system in which a morally sufficient reason for evil is possible. Furthermore, I am not even charged with providing a possible reason. In fact, my theological system should be able to provide reasons for believing that God has a morally sufficient reason for determining the evil in the world even if human beings never know what that reason is.

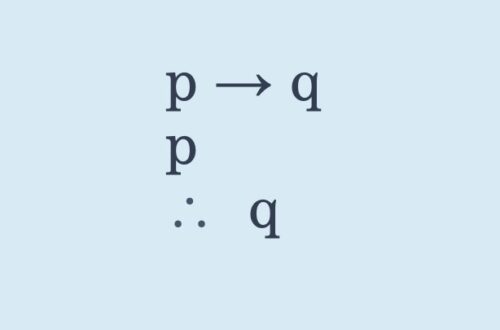

It might be suggested that this is to evade the question. However, the question is about the incoherence of my theological system. And my theological system already accepts the propositions, “God is omnipotent” and “God is good” as necessary truths. I also accept the proposition “evil exists” as a contingent truth. Evil might not have existed and only exists because God determined it to exist, even while God remains unimpeachable for evil’s existence. To see this consider the following argument I borrowed from Greg Bahnsen:

- God is omnipotent

- God is omni-benevolent

- God determines evil (without being morally responsible for it)

- Human beings experience and know evil

- Therefore, God has a morally sufficient reason for determining evil (from 2 – 4)

The addition of (5) is warranted if the Christian is permitted to presuppose (1-2). If the Christian is already committed to the belief in God as omnipotent and omnibenevolent, then (5) is inferred from the premises. If God’s having a morally sufficient reason for permitting and not yet removing evil is an inference, then we do not necessarily have to know what that reason is to solve the problem of evil. In fact, this, I would suggest, is the epistemic condition of most professing Christians who, when asked by their non-Christian friends to supply God’s reason for how the world is reply that they do not know. While this is a difficult proposition to believe (actually, it is impossible if God does not grant us faith), it is not contradictory.

If what I have said solves the internal question of coherence, it might be suggested that it would be deeply implausible to an atheist. While, strictly speaking I am able to solve the logical problem of evil, I am short on persuasiveness. I would agree. However, if there is nothing irrational in holding to the above set of statements, then the fact that I hold to them and an atheist does not indicates that the problem of evil is not a problem of rationality, but one of belief.

How, then, might I offer a persuasive argument? One possible way is to supplement the above argument with an epistemological argument for the necessary existence of an absolutely good God from the human ability to recognize and conceive of evil. Both the atheist and the Christian agree that certain moral actions are intrinsically wrong. Presumably, the problem of evil can only arise if one accepts that some acts are intrinsically wrong. Perhaps both can agree that there is such a thing as moral criteria by which we are able to know evil when we see it. The question is what metaphysic—the Christian one or the atheist one—is consistent with the human ability to recognize, to know, moral evil? The simple answer to this question, for the Christian, is that the existence of the absolutely good God of Christian theism is the necessary condition for the ability of human beings to recognize good and evil.

The implication of what I have said is that human beings could not recognize good and evil if an absolutely good God did not exist. The argument is something like this:

- It is possible for human beings to recognize evil in the world

- Necessarily, if it is possible for human beings to recognize evil in the world, Christian Theism is true

- Christian theism is true

It might be suggested that I am assuming that there is such a thing as objective morality, but what if morality is merely a human construct? Perhaps, but that is certainly not what I believe and it is my system of theology I am defending. I would also contend that most people do not really ascribe to such a view. Francis Schaeffer notes that “in talking to people long enough and deeply enough, and you will find they consider some things are really right and some things are really wrong.”

Moreover, the problem of evil is not a problem at all if what makes an action good or bad is dependent solely on a human opinion of good and evil. The objection relies on the recognition the existence of good and evil in actions themselves not merely in the subjective interpretation of an action.

If we know good and evil because God exists we might ask what it is about the human ability to know God that also allows us to know good and evil (the reader might recognize the following from my previous post). I want to suggest that reason we are able to recognize good and evil is that we are able to know God in such a way as to know his attitude towards us – we are able to know the favor and disfavor of God towards us. To know God’s favor is to be in his goodwill, to be approved of, to be in his good graces. God’s favor is expressed over his creation of human beings in their yet unfallen state (Gen 1:31). Human beings know the disfavor of God in their fallen condition (Rom 1:18). Christ incarnate knew the favor of God (Matt 3:17). It is this favor that human beings find when they place their trust in Christ. We are deemed by God to be good as we are made new in Christ; we are considered as righteous (Gal 3:6) and enjoy God’s grace, his unmerited favor.

But what of people who do not believe in God? How would they know God and his attitude towards them? John Calvin suggested that every human being has a sense of the divine and it is by virtue of which that man has moral knowledge. Alvin Plantinga argues that Calvin thought that the sensus divinitatis makes a human being able to feel guilt. Paul appears to make the same argument. Human beings know God, yet in unrighteousness they suppress that knowledge. Such a knowledge of God also renders a knowledge of self as sinful even while denying this (Rom 1:18-32). If human beings can know their own sinfulness before God and can know God’s goodness, then human beings know what good and evil is.

If the possibility of human beings recognizing what is good and evil has as its necessary condition the existence of God and the knowledge of God, then this has an important epistemological consequence for human beings who attempt to explain evil in our world. It requires the relinquishment of any human ability to stand in judgment over God. As John Frame comments:

God, as sovereign Lord, is the standard of his own actions. He is not subject to human judgment; on the contrary, our judgment is subject to his word. Once we are thus clear on our epistemological situation, we can be assured, despite our questions, of God’s character, for on that matter the Word of God is clear.

This is precisely the opposite posture than the logical problem of evil first supposes. Whereas we begin our discussion hoping to find a way to justify God in the face of evil, we end by wondering what might justify us in the face of God.