I recently heard a talk about teaching in which a teacher was characterized as someone who pours out information into the minds of students. According to the speaker, this is not a good model for education.

In recent years, the idea of a teacher as a dispenser of knowledge to students has become a pariah in education. This is true not only in progressivist circles but also among some classical educators.

It has become so easy to dismiss the idea of a teacher-centered educational model that no argument is needed. In fact, one can dismiss it merely by describing it.

So, let me offer a defense of the dispenser.

Educational models tend to focus on one of three primary realities – ideas, human powers, or the world. Loosely speaking, those who focus on ideas think that the primary reality, the area of most value, is immaterial, immutable, and eternal. Those who focus on human powers are concerned with the proper function of human beings. Those who focus on the world are interested in the way things work and how we can understand the world and the laws of nature. In recent years, some educational theorists consider the notion of fundamental reality to be misguided. For them, an educational model should not focus on reality, but on progress in society.

The least popular of all the three models is the focus on ideas. This has been true in western society at large for about a century and has had a deep effect on educational practices. If ideas are not the most valuable thing in education, then teacher-centerd classrooms will be out of step with everyone else. A teacher-centred classroom is one in which ideas are the most valuable. The teacher has obtained, understood, and then articulates ideas to her students. She dispenses ideas to her students.

The reason, therefore, for a rejection of dispensers cannot be because it is not an effective method, but because ideas are not as valuable in education than either the proper function of human beings or observation of the world. So, a defense of dispensers is a defense of the intrinsic value of ideas.

By ‘idea’ I don’t mean the kind of idea we have when arranging furniture in a room and one person says, “I have an idea. Why don’t we…?” Rather, ideas are immaterial, immutable and eternal. They are discovered not by examining how the world works, but by thought. And rather than focusing on the power to think, a dispenser focuses on what is thought about. Consider truths. A ‘truth’ is shorthand for a ‘true proposition’. A proposition is an object that has a truth value. Call it P. P could be any proposition. For example, perhaps P is ‘two plus two equals four’. This kind of proposition has a kind of necessity to it. It appears to be necessarily true. For a proposition to have this kind of necessity is for it to be impossible that it be false. Plato thought that there are ideas like this in all aspects of life – morality, politics, and religion. For Plato, education is a discovery of these eternal truths.

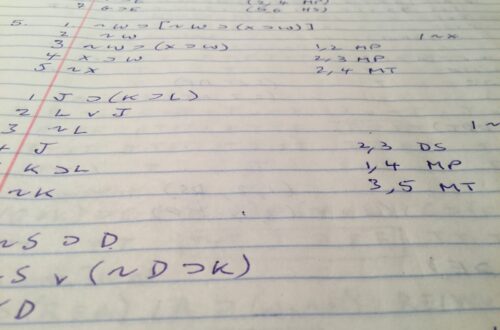

If there are such things as eternal truths, how does that help my defense? Well, for dispensers, eternal truths are of the highest value in education. I teach logic. I teach it not merely because students who can think well can get paid more or that thinking is a proper function of human beings. I teach it because logical truths such as the law of non-contradiction have great intrinsic value. And because I think it has such a high value that I want to instill a love for it. If an art teacher taught about art she did not love, we would find it odd. It is no less odd to teach about ideas and yet to think of them as having less value. Consequently, teachers should love what they dispense and help students to love them as well.

I am also involved in teaching a college class called ‘History of Ideas’. The class is comprised of primary source readings set chronologically along a timeline. Of course, any history teacher worth his or her salt not only teaches what happened, but what ideas drove events. A teacher of the reformation period teaches not only what Luther did but what he thought. But thoughts like these are not things one comes up with by discussing our own thoughts with our friends. We only get them by closely attending to the thoughts of others – by reading sentences that express their thoughts. If that is the only way to get at the thought of Martin Luther, then the only way to get at the thoughts of a person who knows anything is by listening to them express their thoughts in sentences. This is how the dispenser thinks – she has a set of thoughts about a topic, thoughts that have taken years to come by (through attending very carefully to other peoples’ thoughts), and she expresses those thoughts in sentences in a classroom. This does not rule out things like discussion and dialogue, but it does suggest that the teacher’s knowledge is prior to discussion.

Now, you might ask me what makes eternal truths like logical truths valuable? In answer to this, I might point to the intrinsic value of an idea. Anything with intrinsic value is valuable regardless of what effects it might have or whether or not we think it is valuable. Consequently, loving logical truths is not dependent on anything else to make it valuable. However, I might also suggest that ideas are not things floating free out there. They are part of the thoughts of God. Thinking about logical, mathematical, or moral truths is thinking about God’s thoughts. Their value is, therefore, derived from the supreme value of God.

I’m fairly sure that there are dispensers who do not love the content of what they teach. There are teachers who dispense something they don’t think valuable. There are also those teachers who love what they teach, but what they teach is of no value whatsoever. But if a teacher values ideas that are of intrinsic value, then that teacher is a dispenser of great value.

|

| Bad Dispenser? |

It is often said that our loves should be directed primarily at learning. Delight should be in the human power to obtain knowledge. This is a great good and there is no doubt we should love to learn. But the teacher doesn’t just want a student to love to learn, she wants the student to love what he learns. The dispenser teaches with the latter aim in mind. It is a love of truth, beauty and goodness that drives her to teach not just a love of acquiring the ability to learn about those things. For the dispenser, content reigns.

This concludes my defense of the dispenser, but it does not complete what I have to say. What I would like to conclude with is a Christian perspective on these matters.

Let us return to the three main foci of education (and, again, I am ignoring pragmatism and other contemporary theories). Our three areas are ideas, human nature, and the world. In many educational theories one of these three is more fundamental than the others. This basic assumption is reflected naturally in the topics of study and the methods of teaching. For example, a focus on the world will lead to focus on the natural sciences and the methods of observation and interpretation of data.

However, the Christian is not obliged to focus on one of these aspects since all of these aspects find unity in God. God is the eternal mind in whom all eternal truths ‘reside’. Thus, a study of logical truths is a study of the thoughts of God. Education that is focused on the training of the proper function of human beings is a form of education that is focused on the proper training of people made in the image of God. Thus, their proper function is determined by the design of God. Finally, a form of eduction focused on the natural world is a study of God’s world. Laws of nature are what they are because of who God is. Thus, a study of creation assumes the nature of its creator.

Consequently, Christians are not obliged to favor one aspect of imminent reality over another. Indeed, the Christian seeks to integrate all the foci under the transcendent reality of the Lordship of Christ. After all, the main difference between Christian education and secular education is not merely method, but a fundamental commitment to the reality of God, his nature, his creation, and his people.

2 Comments

J. Aaron Seay

If ideas are eternal are they God? I think you and I have had this conversation before, I just can't remember what you said…

Thanks,

Aaron

Ben Holloway

Hi Aaron. Ideas–let's say, propositions, for example–are either eternal and caused by God or eternal and dependent but not caused by God. On the latter view, propositions are God's mental concepts. On the former view, they are abstract objects that God causes to exist (eternally). Neither view entails that ideas are identical to God. Hope that helps!