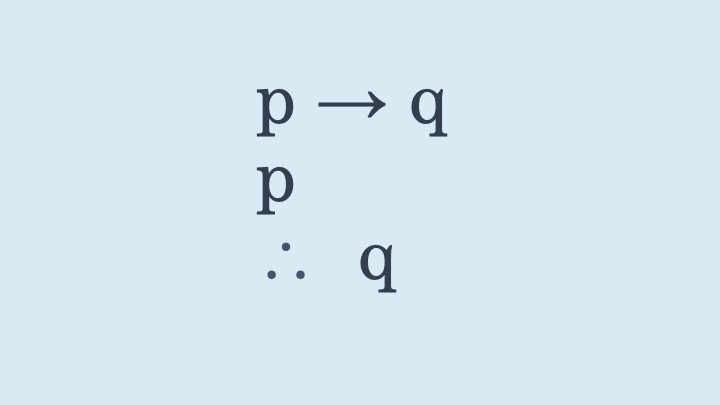

An inference is a kind of intellectual movement. Suppose I consider one belief I might have. I consider what follows from it and, as a result, I come to believe something else. Coming to believe something from something else is an inferential process. Most plausibly, the process involves adhering to a rule of inference. For example, the rule of modus ponens has the following form: if p, then q. p. Therefore, q. If I believe that apples grow on trees and I believe that the fruit I am eating is an apple, I can use modus ponens to infer that the fruit I am eating grew on a tree.

The question is: what kind of process is inference? Is it an automatic computation that takes place without our say so, or is it an activity of some kind involving means-ends intentions? The agency view is highly plausible. As I consider what follows from one belief, I use an inference to form an additional belief. To suppose otherwise, is to invite the view that inferences are compulsive. I don’t so much use them to achieve any goal. Instead, I am passive in their opperation. They occur to me. While this compulsive form of mental state might be the correct way to describe belief formation, it does not appear accurate to describe the act of inference in the same way.

Paul Boghossian defends an agent view. In “Delimiting the Boundaries of Inference,” he writes, “Inference … is a mental behavior and, so, for it to make sense to hold you responsible for your inferences, inferring has to be something you do, and not just something that happens to you. It has to be a mental action of yours, something you have control over, and which you could have done differently, had you thought it desirable to do so” (60).

Notice the significance of taking inference as a form of behavior. Actions are the kinds of things for which agents are responsible. If someone kicks someone else because he is mad, he has done something wrong. In the same way, if an agent fails to infer correctly, it is not merely a matter of malfunction. It is also a matter of responsibility. The agent has failed to meet an obligation. If inference was not a kind of behavior, there would be no obligation to reason correctly. There would just be the fact that a reasoner infers according the rules or not. Of course, whether there are a set of rules of inference that we ought to obey is another matter. But assuming there are some rules, we are obligated to obey them.