How should we do theology? The answer to this question comprises a theological method. A theological method describes how one goes about doing theology. Theological Reflection (TR) is a recently developed theological method. Its roots are in theologies that stress a particular cultural context as the starting point for theology. Over the last few decades, TR has become more mainstream, making its way into seminaries and influencing some in the evangelical community.

In this post I want to explain the method of TR and argue that to make it the dominant method for the theological task is a mistake.

TR Begins and Ends with Experience

All methods have to start somewhere. The starting point for TR is the lived experience of those doing theology. As Robert Kinast suggests, TR “begins with the lived experience of those doing the reflection; it correlates this experience with the sources of the Christian tradition; and it draws out practical implications for Christian living.”

In contrast to traditional methods, TR begins and ends in praxis – some experience leads to reflection and analysis that, in turn, leads to new forms of practice in the Christian life: “Theology is in service to experience, not the other way round.”

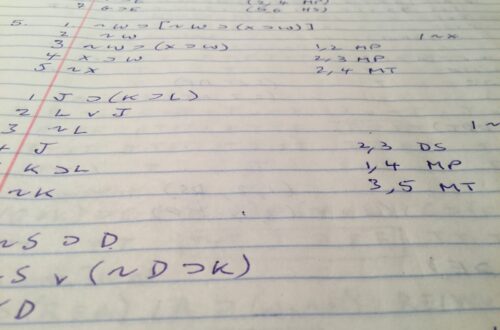

There are numerous versions of TR, but they all follow a similar process. For example, Thomas Groome suggests five stages. First, the relevant experience is named. To name an experience involves simultaneously describing and interpreting an experience. In this stage the experience is owned in the sense that the subject becomes responsible for the narrative and its interpretation.

The second stage is to reflect on the experience, arriving at unresolved questions and tensions. It also involves a critique of one’s prejudices and presuppositions. This process is a clarifying process, bringing to light the experience in order to best move to the third stage – research. In the research stage the experience is correlated to relevant theory found within the Christian tradition. All such theories are brought to bear on the issues that the experience has raised.

The fourth movement is a dialectic between the subject’s experience and the correlating resources in the Christian tradition. The assumption in this stage is that faith (the resources of the tradition) and human experience naturally correlate in the learner: “People have a natural capacity to make such connections between life and faith and to act on them.” Faith and learning, therefore, find their integrative moment within one’s experience.

Finally, what results from the process is a decision to act. God’s work in revelation, according to Groome, is found primarily in action not in propositions. Consequently, praxis is the desired learning outcome. Participants are continually enabled to reflect on human experience with the primary aim to develop new strategies for living out the Christian faith in the world.

What’s Wrong With TR?

Many proponents of TR are correct when they say that TR is a somewhat natural way to do theology. It is not wrong to seek help with troubling experiences from our theological resources. What is faulty is the promotion of TR to the dominant method for theology. Here are four reasons to reject TR.

First, the starting point for a theology limits the content of a theology. If the starting point for theology is our present lived experience, then it will limit and determine the outcome or content of theology. Instead, the starting point for Christian theology ought to be God’s revelation in scripture and it should be scripture that determines the outcome of theology. That is not to say experience is irrelevant, but only that experience makes sense in the light of scripture not the other way round.

Second, in TR, the place of scripture is often limited to being a resource among others used in order to aid reflection. TR lowers the place of scripture to the role of a “means” for reflection. The Bible’s historical nature is lost in a hermeneutic that focuses on the existential reality of the reader.

Third, TR makes cultural context king of one’s hermeneutic. The underlying assumption is that every culture or individual needs its own theology. Such a supposition drives interpretation leading to an opposition to anything like a “grammatical historical” method of interpretation. This is because the context that drives a grammatical historical hermeneutic is the context in which the Bible was written not in which it is read.

Finally, though a practitioner of TR might not realize it, the method is derived from a theory of truth called pragmatism. Pragmatists argue that statements are not true in virtue of their relationship with the world. Instead they are true if and only if they have a high degree of utility when believed. Thus, pragmatists often see learning as a form of problem solving. Applied to theology, pragmatists are interested in how theological resources address our problems. Truth is what has a high degree of utility for our lived experience.

In contrast, a more traditional view of truth holds that what makes any statement true is its relationship with the world. At a minimum, a statement is true if and only if it corresponds, or is in harmony with, a state of affairs in the world. According to this view of truth, the truth of a statement is not dependent upon anyone believing in it and does not depend on its utility in the life of the believer. Although a full defense of the correspondence theory of truth would take too much time for a blog post, suffice to say that it should be preferred to the pragmatist theory. TR emphasizes (and perhaps even depends on) a pragmatist theory. To adopt it, when one holds to a correspondence theory is to adopt a method not well-fitted (or even incompatible) with one’s theoretical assumptions.

You can find a good summary of TR in Robert Kinast, What Are They Saying About Theological Reflection? (Paulist Press, 2000).