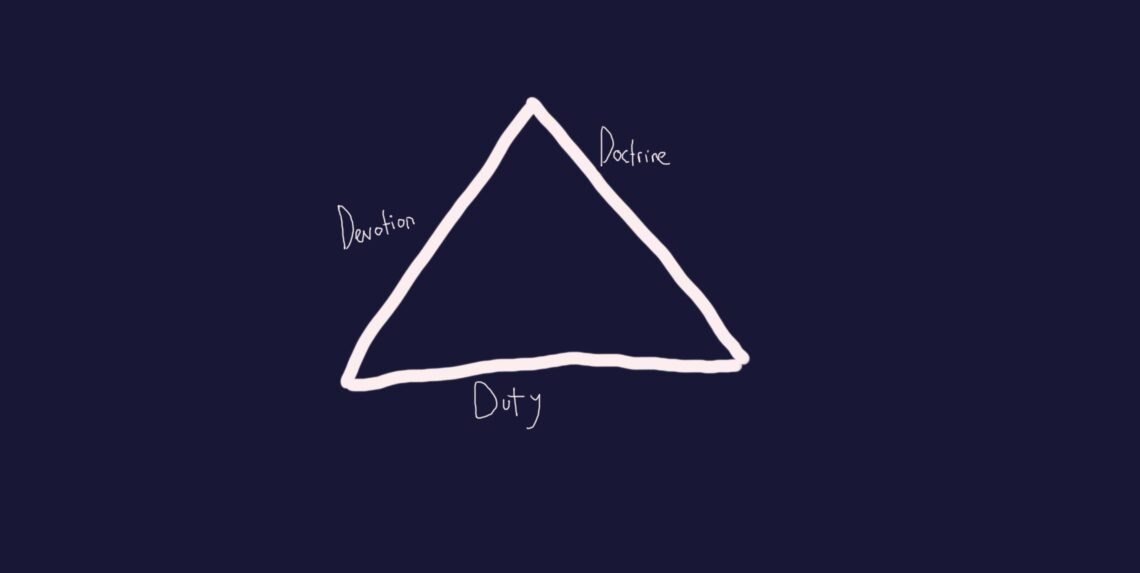

If I say, “I know God,” I am telling you that I am personally acquainted with him. If I say, “I know that God is omnipotent,” I am telling you that I have good reason to believe that the proposition expressed in that sentence is true. If I say, “I am obeying the command to love God by obeying his command to serve others,” I am telling you something about my activities. I am telling you about an obligation to perform an action and the fact that I am meeting it.

All three of these aspects relate to one another in crucial ways. For example, I can’t have a personal acquaintance with anybody I know nothing about. If I am acquainted with God, I know some facts about him. It is, thus, necessary, but not sufficient, that I know something about God for having an aquaintance with him.

It is quite possible to know about God and be unaquainted with him. An atheist may be an expert on doctrine. Indeed, one occasionally hears or reads a person write eloquently and insightfully about what the Bible teaches all the while having no interest in having a relationship with the God of the Bible.

It is often said that those who don’t obey God don’t really know him. What those who say this are usually suggesting is that doctrine and devotion are jointly sufficient for obedience. It should be added that the enabling power of the Spirit is included in devotion. For it is impossible to be rightly acquainted with God without the redemptive work of the Holy Spirit. Of course, there are degrees of epistemic certainty when it comes to this relationship. Being in the possession of right doctrine and devotion at one point in a person’s life does not entail the same degree of doctrinal knowledge nor the same proximity of acquaintance at another time of life. Thus, there is a certain degree of instability when it comes to judging the state of one’s soul by considering the actions one has performed at a particular time. Thus, as many good counselors have told the anxious – it is better to judge by considering the whole rather than the part of one’s Christian walk.

A less considered relationship holds between devotion and the other two. Might it be the case that knowledge of doctrine and obedience to commands are jointly sufficient for devotion? Some consider theology to be a practical concern. The scripture is the ‘script’ for the ‘drama of doctrine’ (see Kevin Vanhoozer’s masterful treatment of this analogy in The Drama of Doctrine). One takes up the Bible as a sort of script and conducts oneself as an actor. One’s life is supposed to be a public witness precisely because it is lived according to a certain drama including the dramas of the incarnation, crucifixion and redemption. If one lives a life as if one is part of the play, one develops, as the drama develops, a certain devotion to the plot-line. By doing so, one also develops a devotion to the author of the script.

In the philosophical discipline of epistemology, the study of propositional knowledge is of primary importance. However, acquaintance knowledge and know-how are not ignored. What epistemologists recognize, however, is that all three domains are legitimate and related to one another in significant ways. One must be careful, however, to avoid emphasis leading to avoidance. Sometimes, Christians will say that one or two forms of knowledge are unimportant. “What matters is not doctrine” they say. “It is relationship.” Or, another might say, “I just do as I’m told. What do I care about the fancy words of doctrine?” There are even those who claim that one kind of knowledge can be reduced to another. They might say, “I don’t require good motives, only good actions,” as if to suggest that devotion can be reduced to duty. Still others suggest that one or other is epiphenomenal, a sort of subjective side effect of the other two. Having a real personal relationship with God is not possible though it might feel like it.

Instead of reductions or dismissals, the Christian must embrace all three forms of relationship. We must seek to know about God, know him personally, and act rightly. We also seek to do one with full acceptance that it relates to the others. We obey because we know God’s commands and desire to fulfill our obligations to the one who loves us. We seek to know about God because we love him. We love him only if we know who he is. And, as we act according to God’s prescriptions, our love for him is strengthened.